"Mathura A District Memoir Chapter-11" के अवतरणों में अंतर

अश्वनी भाटिया (चर्चा | योगदान) |

अश्वनी भाटिया (चर्चा | योगदान) |

||

| पंक्ति १४: | पंक्ति १४: | ||

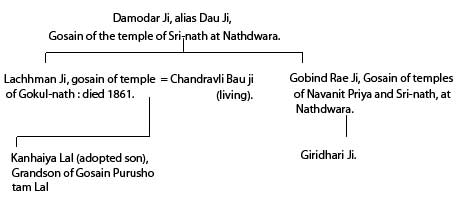

At the foot of the hill on one side is the little village of Jatipura with several temples, of which one, dedicated to Gokul-nath, though a very mean building in appearance, has considerable local celebrity. Its head is the Gosain of the temple with the same title at Gokul, and it is the annual scene of two religious solemnities, both celebrated on the day after the Dip-dan at Gobardhan. The first is the adoration of the sacred hill, called the Giri-raj Puja, and the second the Anna-Kut, or commemoration of Krishna's sacrifice. They are always accompanied by the renewal of a long-standing dispute be tween the priests of the two rival temples of Sri-nath and Gokul-nath, the one of whom supplies the god, the other his shrine. The image of Gokul-nath, the traditional object of veneration, is brought over for the occasion from Gokul, and throughout the festival is kept in the Gokul-nath temple on the hill, except for a few hours on the morning after the Diwali, when it is exposed for worship on a separate pavilion. This building is the property of Giridhari Ji, the Sri-nath Gosain, who invariably protests against the intrusion. Party-feeling runs so high that it is generally found desirable a little before the anniversary to take heavy security from the principals on either side that there shall be no breach of the peace. The relationship between the Gosains is explained by the following table:— | At the foot of the hill on one side is the little village of Jatipura with several temples, of which one, dedicated to Gokul-nath, though a very mean building in appearance, has considerable local celebrity. Its head is the Gosain of the temple with the same title at Gokul, and it is the annual scene of two religious solemnities, both celebrated on the day after the Dip-dan at Gobardhan. The first is the adoration of the sacred hill, called the Giri-raj Puja, and the second the Anna-Kut, or commemoration of Krishna's sacrifice. They are always accompanied by the renewal of a long-standing dispute be tween the priests of the two rival temples of Sri-nath and Gokul-nath, the one of whom supplies the god, the other his shrine. The image of Gokul-nath, the traditional object of veneration, is brought over for the occasion from Gokul, and throughout the festival is kept in the Gokul-nath temple on the hill, except for a few hours on the morning after the Diwali, when it is exposed for worship on a separate pavilion. This building is the property of Giridhari Ji, the Sri-nath Gosain, who invariably protests against the intrusion. Party-feeling runs so high that it is generally found desirable a little before the anniversary to take heavy security from the principals on either side that there shall be no breach of the peace. The relationship between the Gosains is explained by the following table:— | ||

| − | [[Image:Table-Growse-4.jpg | + | [[Image:Table-Growse-4.jpg|center]] |

Immediately opposite Jatipura, and only parted from it by the intervening range, is the village of Anyor—literally ‘the other side’—with the temple of Sri-nath on the summit between them. A little distance beyond both is the village of Puchhri, which, as the name denotes, is considered the ' extreme limit' of the Giri-raj. | Immediately opposite Jatipura, and only parted from it by the intervening range, is the village of Anyor—literally ‘the other side’—with the temple of Sri-nath on the summit between them. A little distance beyond both is the village of Puchhri, which, as the name denotes, is considered the ' extreme limit' of the Giri-raj. | ||

| − | Kartik, the month in which most of Krishna's exploits are believed to have been performed, is the favorite time for the pari-krama, or ‘perambulation’ of the sacred hill. The dusty circular road which winds around its base has a length of seven kos, that is, about twelve miles, and is frequently measured by devotees who at every step prostrate themselves at full length. When flat on the ground, they mark a line in the sand as far as their hands can reach, then rising they prostrate themselves again from the line so marked, and continue in the same style till the whole weary circuit has been accomplished. This ceremony, called Dandavati pari-krama, occupies from a week to a fortnight, and is generally performed for wealthy sinners vicariously by the Brahmans of the place, who receive from Rs. 50 to Rs. 100 for their trouble and transfer all the merit of the act to their employers. The ceremony has been performed with a hundred and eight. | + | Kartik, the month in which most of Krishna's exploits are believed to have been performed, is the favorite time for the pari-krama, or ‘perambulation’ of the sacred hill. The dusty circular road which winds around its base has a length of seven kos, that is, about twelve miles, and is frequently measured by devotees who at every step prostrate themselves at full length. When flat on the ground, they mark a line in the sand as far as their hands can reach, then rising they prostrate themselves again from the line so marked, and continue in the same style till the whole weary circuit has been accomplished. This ceremony, called Dandavati pari-krama, occupies from a week to a fortnight, and is generally performed for wealthy sinners vicariously by the Brahmans of the place, who receive from Rs. 50 to Rs. 100 for their trouble and transfer all the merit of the act to their employers. The ceremony has been performed with a hundred and eight. <ref>.In Christian mysticism 107 is as sacred a number as 108 in Hindu. Thus the Emperor Justiman's great church of S. Sophia at Constantinople was supported by 107 columns, the number of pillars in the House of Wisdom.</ref> prostrations at each step (that being the number of Radha's names and of the beads in a Vaishnava rosary), it then occupied some two years, and was remunerated by a donation of Rs. 1,000. |

| − | About the centre of the range stands the town of Gobardhan on the margin of a very large irregularly shaped masonry tank, called the Manasi Ganga, supposed to have been called into existence by the mere action of the divine will (manasa). At one end the boundary is formed by the jutting crags of the holy hill; on all other sides the water is approached by long flights of stone steps. It has frequently been repaired at great cost by the Rajas of Bharat-pur; but is said to have been originally constructed in its present form by Raja Man Sinh of Jaypur, whose father built the adjoining temple of Harideva. There is also at Banaras a tank constructed by Man Sinh, called Man Sarovar, and by it a temple dedicated to Manesvar: facts which suggest a suspicion that the name ‘Manasi’ ( | + | About the centre of the range stands the town of Gobardhan on the margin of a very large irregularly shaped masonry tank, called the Manasi Ganga, supposed to have been called into existence by the mere action of the divine will (manasa). At one end the boundary is formed by the jutting crags of the holy hill; on all other sides the water is approached by long flights of stone steps. It has frequently been repaired at great cost by the Rajas of Bharat-pur; but is said to have been originally constructed in its present form by Raja Man Sinh of Jaypur, whose father built the adjoining temple of Harideva. There is also at Banaras a tank constructed by Man Sinh, called Man Sarovar, and by it a temple dedicated to Manesvar: facts which suggest a suspicion that the name ‘Manasi’ <ref>In devotional literature manasi has the sense of 'spiritual,' as in the Catholic phrase ' spiritual communion.' Thus it is related in the Bhakt Mala that Raja Prithiraj, of Bikaner, being on a journey and unable to visit the shrine, for which he had a special devotion, imagined himself to be worshipping in the temple, and made a spiritual act of contemplation before the image (murti ka dhyan manasi karte the). For two days his aspirations seemed to meet with no response, but on the third he became conscious of the divine presence. On enquiry it' was found that for two days the god had been removed elsewhere, while the temple was under repair. He then made a vow to end his days at Mathura. The emperor, to spite him, put him in command of an expedition to kabul; but when he felt his end approaching, he mounted a camel and hastened back to the holy city and there expired. </ref> is of much less antiquity than is popularly believed. Unfortunately, there is neither a natural spring, nor any constant artificial supply of water, and for half the year the tank is always dry. But ordinarily at the annual illumination, or Dip-dan, which occurs soon after the close of the rains, during the festival of the Diwali, a fine broad sheet of water reflects the light of the innumerable lamps, which are ranged tier above tier along the ghats and adjacent buildings, by the hundred thousand pilgrims with whom the town is then crowded. |

In the year 1871, as there was no heavy rain towards the. end of the season, and the festival of the Diwali also fell later than usual, it so happened that on the bathing day, the 12th of November, the tank was entirely dry, with the exception of two or three green and muddy little puddles. To obviate this mischance, several holes were made and wells sunk in the area of the tank, with one large pit, some 30 feet square and as many deep, in whose turbid waters many thousand pilgrims had the happiness of immersing themselves. For several hours no less than twenty-five persons a minute continued to descend, and as many to ascend, the steep and slippery steps; while the yet more fetid patches of mud and water in other parts of the basin were quite as densely crowded. At night, the vast amphitheatre, dotted with groups of people and glimmering circles of light, presented a no less picturesque appearance than in previous years when it was a brimming lake. To the spectator from the garden side of the broad and deep expanse, as the line of demarkation between the steep flights of steps and the irregular masses of building which immediately sur mount them ceased to be perceptible, the town presented the perfect semblance of a long and lofty mountain range dotted with fire-lit villages; while the clash of cymbals, the beat of drums, the occasional toll of bells from the adjoining temples, with the sudden and long-sustained cry of some enthusiastic band, vociferating the praises of mother Ganga, the clapping of hands that began scarce heard, but was quickly caught up and passed on from tier to tier, and prolonged into a wild tumult of applause,—all blended with the ceaseless mur mur of the stirring crowd in a not discordant medley of exciting sound. Accord ing to popular belief, the ill-omened drying up of the water, which had not occurred before in the memory of man, was the result of the curse of one Habib-ullah Shah, a Muhammadan fakir. He had built himself a hut on the top of the Giri-raj, to the annoyance of the priests of the neighbouring temple of Dan-Rae, who complained that the holy ground was defiled by the bones and other fragments of his unclean diet, and procured an order from the Civil Court for his ejectment. Thereupon the fakir disappeared, leaving a curse upon his persecutors; and this bore fruit in the drying up of the healing waters of the Manasi Ganga. | In the year 1871, as there was no heavy rain towards the. end of the season, and the festival of the Diwali also fell later than usual, it so happened that on the bathing day, the 12th of November, the tank was entirely dry, with the exception of two or three green and muddy little puddles. To obviate this mischance, several holes were made and wells sunk in the area of the tank, with one large pit, some 30 feet square and as many deep, in whose turbid waters many thousand pilgrims had the happiness of immersing themselves. For several hours no less than twenty-five persons a minute continued to descend, and as many to ascend, the steep and slippery steps; while the yet more fetid patches of mud and water in other parts of the basin were quite as densely crowded. At night, the vast amphitheatre, dotted with groups of people and glimmering circles of light, presented a no less picturesque appearance than in previous years when it was a brimming lake. To the spectator from the garden side of the broad and deep expanse, as the line of demarkation between the steep flights of steps and the irregular masses of building which immediately sur mount them ceased to be perceptible, the town presented the perfect semblance of a long and lofty mountain range dotted with fire-lit villages; while the clash of cymbals, the beat of drums, the occasional toll of bells from the adjoining temples, with the sudden and long-sustained cry of some enthusiastic band, vociferating the praises of mother Ganga, the clapping of hands that began scarce heard, but was quickly caught up and passed on from tier to tier, and prolonged into a wild tumult of applause,—all blended with the ceaseless mur mur of the stirring crowd in a not discordant medley of exciting sound. Accord ing to popular belief, the ill-omened drying up of the water, which had not occurred before in the memory of man, was the result of the curse of one Habib-ullah Shah, a Muhammadan fakir. He had built himself a hut on the top of the Giri-raj, to the annoyance of the priests of the neighbouring temple of Dan-Rae, who complained that the holy ground was defiled by the bones and other fragments of his unclean diet, and procured an order from the Civil Court for his ejectment. Thereupon the fakir disappeared, leaving a curse upon his persecutors; and this bore fruit in the drying up of the healing waters of the Manasi Ganga. | ||

| पंक्ति २७: | पंक्ति २७: | ||

Bihari Mall, the father of the reputed founder, was the first Rajput who attached himself to the court of a Muhammandan emperor. He was chief of the Rajawat branch of the Kanchhwaha Thakurs seated at Amber, and claimed to be eighteenth in descent from the founder of the family. The capital was subsequently transferred to Jaypur in 1728 A.D.; the present Maharaja being the thirty-fourth descendant of the original stock. In the battle of Sarnal, Bhagawan Das had the good fortune to save Akbar's life, and was subsequently appointed Governor of the Panjab. He died about the year 1590 at Lahor. His daughter was married to prince Salim, who eventually became emperor under the title of Jahargir; the fruit of their marriage being the unfortunate prince Khusru. | Bihari Mall, the father of the reputed founder, was the first Rajput who attached himself to the court of a Muhammandan emperor. He was chief of the Rajawat branch of the Kanchhwaha Thakurs seated at Amber, and claimed to be eighteenth in descent from the founder of the family. The capital was subsequently transferred to Jaypur in 1728 A.D.; the present Maharaja being the thirty-fourth descendant of the original stock. In the battle of Sarnal, Bhagawan Das had the good fortune to save Akbar's life, and was subsequently appointed Governor of the Panjab. He died about the year 1590 at Lahor. His daughter was married to prince Salim, who eventually became emperor under the title of Jahargir; the fruit of their marriage being the unfortunate prince Khusru. | ||

| − | The temple has a yearly income of some Rs. 2,300, derived from the two villages, Bhagosa and Lodhipuri, the latter estate being a recent grant, in lien of an annual money donation of Rs. 500, on the part of the Raja of Bharat-pur, who further makes a fixed monthly offering to the shrine at the rate of one rupee per diem. The hereditary Gosains have long devoted the entire income to their own private uses, completely neglecting the fabric of the temple and its religious services.’ | + | The temple has a yearly income of some Rs. 2,300, derived from the two villages, Bhagosa and Lodhipuri, the latter estate being a recent grant, in lien of an annual money donation of Rs. 500, on the part of the Raja of Bharat-pur, who further makes a fixed monthly offering to the shrine at the rate of one rupee per diem. The hereditary Gosains have long devoted the entire income to their own private uses, completely neglecting the fabric of the temple and its religious services.’ <ref>The estate is divided into twenty-four bats or shares, allotted among seventeen different families. It appeared that all were agreed as to the distribution, with the exception of one man by name Narayan, who is addition, to his own original share, claimed also as sole representative of a shareholder deceased. This claim was not admitted by the others, and the zamindars continued to pay the revenue as a deposit into the district treasury, till eventually the muafldars concurred in making a joint-application for its transfer to themselves.</ref> In consequence of such short-sighted greed, the votive offerings at this, one of the most famous shrines in Upper India, have dwindled down to about Rs. 50 a year. Not only so, but, early in 1872, the roof of the nave, which had hitherto been quite perfect, began to give way. An attempt was made by the writer of this memoir to procure an order from the Civil Court authorizing the expenditure, on the repair of the fabric, of the proceeds of the temple estate, which, in consequence of the dispute among the shareholders, had for some months past been paid as a deposit into the district treasury and had accumulated to more than Rs. 3,000. There was no unwillingness on the part of the local Government to further the proposal, and an engineer was deputed to examine and report on the probable cost. But an unfortunate delay occurred in the Commissioner's office, the channel of correspondence, and meanwhile the whole of the roof fell in, with the exception of one compartment. This, however, would have been sufficient to serve as a model in the work of restora tion. The estimate was made out for Rs. 8,767; and as there was a good balance in hand to begin upon, operations might have been commenced at once and completed without any difficulty in the course of two or three years. But no further orders were communicated by the superior authorities from April, when the estimate was submitted, till the following October, and in the interim a baniya from the neighbouring town of Aring, by name Chhitar Mall, hoping to immortalise himself at a moderate outlay, came to the relief of the temple proprietors and undertook to do all that was necessary at his own private cost. He accordingly ruthlessly demolished all that yet remained of the original roof, breaking down at the same time not a little of the curious cornice, and in its place simply threw across, from wall to wall, rough and unshapen wooden beams, of which the best that can be said is, that they may, for some few years, serve as a protection' from the weather. But all that was unique and characteristic in the design has ceased to exist; and thus another of the few pages in the fragmentary annals of Indian architecture has been blotted out for ever. Like the temple of Gobind Deva at Brinda-ban, it has none of the coarse figure sculpture which detract so largely from the artistic appearance of most Hindu religious buildings; and though originally consecrated to idolatrous worship, it was in all points of construction equally well adapted for the public ceremonial of the purest faith. Had it been preserved as a national monument, it might at some day, in the future golden age, have been to Gobardhan what the Pagan Pantheon is now to Christian Rome. |

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

__INDEX__ | __INDEX__ | ||

०५:४३, २४ अप्रैल २०१० का अवतरण

AT a distance of three miles from the city of Mathura, the road to Gobar dhan runs through the village of Satoha, by the side of a large tank of very sacred repute, called Santanu Kund. The name commemorates a Raja Santanu who (as is said 'on the spot) here practised, through a long course of years, the severest religious austerities in the hope of obtaining a son. His wishes were at last gratified by a union with the goddess Ganga, who bore him Bhishma, one of the famous heroes of the Mahabharat. Every Sunday the place is frequented by women who are desirous of issue, and a large fair is held there on the 6th of the light fortnight of Bhadon. The tank, which is of very considerable dimensions, was faced all round with stone, early last century, by Sawai Jay Sinh of Amber, but a great part of the masonry is now much dilapidated. In its centre is a high hill connected with the main land by a bridge. The sides of the island are covered with fine ritha trees, and on the summit, which is approached by a flight of fifty stone steps, is a small temple. Here it is incum bent upon the female devotees, who would have their prayers effectual, to make some offering to the shrine, and inscribe on the ground or wall the mystic device called in Sanskrit Svastika and in Hindi Sathiya, the fylfot of Western eccle siology. The local superstition is probably not a little confirmed by the acci dental resemblance that the king's name bears to the Sanskrit word for ‘children,’ santana. For, though Raja Santanu is a mythological personage of much ancient celebrity, being mentioned not only in several of the Puranas, but also in one of the hymns of the Rig Veda, he is not much known at the present day, and what is told of him at Satoha is a very confused jumble of the original legend. The signal and, according to Hindu ideas, absolutely fearful abnegation of self, there ascribed to the father, was undergone for his gratification by the dutiful son, who thence derived his name of Bhishma, ‘the fearful.’ For, in extreme old age, the Raja was anxious to wed again, but the parents of the fair girl on whom he fixed his affections would not consent to the union, since the fruit of the marriage would be debarred by Bhishma's seniority from the succession to the throne. The difficulty was removed by Bhishma's filial devotion, who took an oath to renounce his birthright and never to beget a son to revive the claim. Hence every religious Hindu accounts it a duty to make him amends for this want of direct descendants by once a year offering libations to Bhishma's spirit in the same way as to one of his own ancestors. The formula to be used is as follows:—" I present this water to the childless hero, Bhishma, of the race of Vyaghrapada, the chief of the house of Sankriti. May Bhishma, the son of Santanu, the speaker of truth and subjugator of his passions, obtain by this water the oblations due from sons and grandsons."

The story in the Nirukta Vedanga relates to an earlier period in the king's life, if, indeed, it refers to the same personage at all, which has been doubted. It is there recorded that, on his father's death, Santanu took possession of the throne, though he had an elder brother, by name Devapi, living. This violation of the right of primogeniture caused the land to be afflicted with a drought of twelve years' continuance, which was only terminated by the recita tion of a hymn of prayer (Rig Veda, x., 98) composed by Devapi himself, who had voluntarily adopted the life of a religious. The name Satoha is absurdly derived by the Brahmans of the place from sattu, ' bran,' which is said to have been the royal ascetic's only diet. In all probability it is formed from the word Santanu itself, combined with some locative affix, such as sthana.

Ten miles further to the west is the famous place of Hindu pilgrimage, Gobardhan, i.e., according to the literal meaning of the Sanskrit compound, the nurse of cattle.' The town, which is of considerable size, with a population of 4,944, occupies a break in a narrow range of hill, which rises abruptly from the alluvial plain, and stretches in a south-easterly direction for a distance of some four or five miles, with an average elevation of about 100 feet.

This is the hill which Krishna is fabled to have held aloft on the tip of his finger for seven days and nights to cover the people of Braj from the storms poured down upon them by Indra when deprived of his wonted sacrifices. In pictorial representations it always appears as an isolated conical peak, which is as unlike the reality as possible. It is ordinarily styled by Hindus of the present day the Giri-raj, or royal hill, but in earlier literature is more frequently designated the Anna-kut. There is a firm belief in the neighbourhood that, as the waters of the Jamuna are yearly decreasing in body, so too the sacred hill is steadily diminishing in height; for in past times it was visible from Aring, a town four or five miles distant, whereas now a few hundred yards are sufficient to remove it from sight. It may be hoped that the marvellous fact reconciles the credulous pilgrim to the insignificant appearance presented by the object of his adoration. It is accounted so holy that not a particle of the stone is allowed to be taken for any building purpose; and even the road which crosses it at its lowest point, where only a few fragments of the rock crop up above the ground, had to be carried over them by a paved causeway.

The ridge attains its greatest elevation towards the south between the vil lages of Jati pura and Anyor. Here, on the submit, was an ancient temple founded in the year 1520 A. D., by the famous Vallabhacharya of Gokul, and dedicated to Sri-nath. In anticipation of one of Aurangzeb's raids, the image of the god was removed to Nathdwara in Udaypur territory, and has remained there ever since. The temple on the Giri-raj was thus allowed to fall into ruin, and the wide walled enclosure now exhibits only long lines of foundations and steep flights of steps, with a small, uutenanted, and quite modern shine. The plateau, however, commands a very extensive view of the neighbouring coun ty, both on the Mathura and the Bharatpur side, with the fort of Dig and the heights of Nand-ganw and Barsana in the distance.

At the foot of the hill on one side is the little village of Jatipura with several temples, of which one, dedicated to Gokul-nath, though a very mean building in appearance, has considerable local celebrity. Its head is the Gosain of the temple with the same title at Gokul, and it is the annual scene of two religious solemnities, both celebrated on the day after the Dip-dan at Gobardhan. The first is the adoration of the sacred hill, called the Giri-raj Puja, and the second the Anna-Kut, or commemoration of Krishna's sacrifice. They are always accompanied by the renewal of a long-standing dispute be tween the priests of the two rival temples of Sri-nath and Gokul-nath, the one of whom supplies the god, the other his shrine. The image of Gokul-nath, the traditional object of veneration, is brought over for the occasion from Gokul, and throughout the festival is kept in the Gokul-nath temple on the hill, except for a few hours on the morning after the Diwali, when it is exposed for worship on a separate pavilion. This building is the property of Giridhari Ji, the Sri-nath Gosain, who invariably protests against the intrusion. Party-feeling runs so high that it is generally found desirable a little before the anniversary to take heavy security from the principals on either side that there shall be no breach of the peace. The relationship between the Gosains is explained by the following table:—

Immediately opposite Jatipura, and only parted from it by the intervening range, is the village of Anyor—literally ‘the other side’—with the temple of Sri-nath on the summit between them. A little distance beyond both is the village of Puchhri, which, as the name denotes, is considered the ' extreme limit' of the Giri-raj.

Kartik, the month in which most of Krishna's exploits are believed to have been performed, is the favorite time for the pari-krama, or ‘perambulation’ of the sacred hill. The dusty circular road which winds around its base has a length of seven kos, that is, about twelve miles, and is frequently measured by devotees who at every step prostrate themselves at full length. When flat on the ground, they mark a line in the sand as far as their hands can reach, then rising they prostrate themselves again from the line so marked, and continue in the same style till the whole weary circuit has been accomplished. This ceremony, called Dandavati pari-krama, occupies from a week to a fortnight, and is generally performed for wealthy sinners vicariously by the Brahmans of the place, who receive from Rs. 50 to Rs. 100 for their trouble and transfer all the merit of the act to their employers. The ceremony has been performed with a hundred and eight. [१] prostrations at each step (that being the number of Radha's names and of the beads in a Vaishnava rosary), it then occupied some two years, and was remunerated by a donation of Rs. 1,000.

About the centre of the range stands the town of Gobardhan on the margin of a very large irregularly shaped masonry tank, called the Manasi Ganga, supposed to have been called into existence by the mere action of the divine will (manasa). At one end the boundary is formed by the jutting crags of the holy hill; on all other sides the water is approached by long flights of stone steps. It has frequently been repaired at great cost by the Rajas of Bharat-pur; but is said to have been originally constructed in its present form by Raja Man Sinh of Jaypur, whose father built the adjoining temple of Harideva. There is also at Banaras a tank constructed by Man Sinh, called Man Sarovar, and by it a temple dedicated to Manesvar: facts which suggest a suspicion that the name ‘Manasi’ [२] is of much less antiquity than is popularly believed. Unfortunately, there is neither a natural spring, nor any constant artificial supply of water, and for half the year the tank is always dry. But ordinarily at the annual illumination, or Dip-dan, which occurs soon after the close of the rains, during the festival of the Diwali, a fine broad sheet of water reflects the light of the innumerable lamps, which are ranged tier above tier along the ghats and adjacent buildings, by the hundred thousand pilgrims with whom the town is then crowded.

In the year 1871, as there was no heavy rain towards the. end of the season, and the festival of the Diwali also fell later than usual, it so happened that on the bathing day, the 12th of November, the tank was entirely dry, with the exception of two or three green and muddy little puddles. To obviate this mischance, several holes were made and wells sunk in the area of the tank, with one large pit, some 30 feet square and as many deep, in whose turbid waters many thousand pilgrims had the happiness of immersing themselves. For several hours no less than twenty-five persons a minute continued to descend, and as many to ascend, the steep and slippery steps; while the yet more fetid patches of mud and water in other parts of the basin were quite as densely crowded. At night, the vast amphitheatre, dotted with groups of people and glimmering circles of light, presented a no less picturesque appearance than in previous years when it was a brimming lake. To the spectator from the garden side of the broad and deep expanse, as the line of demarkation between the steep flights of steps and the irregular masses of building which immediately sur mount them ceased to be perceptible, the town presented the perfect semblance of a long and lofty mountain range dotted with fire-lit villages; while the clash of cymbals, the beat of drums, the occasional toll of bells from the adjoining temples, with the sudden and long-sustained cry of some enthusiastic band, vociferating the praises of mother Ganga, the clapping of hands that began scarce heard, but was quickly caught up and passed on from tier to tier, and prolonged into a wild tumult of applause,—all blended with the ceaseless mur mur of the stirring crowd in a not discordant medley of exciting sound. Accord ing to popular belief, the ill-omened drying up of the water, which had not occurred before in the memory of man, was the result of the curse of one Habib-ullah Shah, a Muhammadan fakir. He had built himself a hut on the top of the Giri-raj, to the annoyance of the priests of the neighbouring temple of Dan-Rae, who complained that the holy ground was defiled by the bones and other fragments of his unclean diet, and procured an order from the Civil Court for his ejectment. Thereupon the fakir disappeared, leaving a curse upon his persecutors; and this bore fruit in the drying up of the healing waters of the Manasi Ganga.

Close by is the famous temple of Hari-deva, erected during the tolerant reign of Akbar by Raja Bhagawan Das of Amber on a site long previously occupied by a succession of humbler fanes. It consists of a nave 68 feet in length and 20 feet broad, leading to a choir 20 feet square, with a sacrarium of about the same dimensions beyond. The nave has four openings on either side, of which three have arched heads, while the fourth nearest the door is covered by a square architrave supported by Hindu brackets. There are clerestory windows above, and the height is about 30 feet to the cornice, which is decorated at intervals with large projecting heads of elephants and sea-monsters. There was a double roof, each entirely of stone: the outer one a high pitched gable, the inner an arched ceiling, or rather the nearest approach to an arch ever seen in Hindu design. The centre was really flat, but it was so deeply coved at the sides that, the width of the building being inconsiderable, it had all the effect of a vault, and no doubt suggested the possibility of the true radiating vault, which we find in the temple of Govind Deva built by Bhagawan's son and successor, Man Sinh at Brinda-ban. The construction is extremely massive, and even the exterior is still solemn and imposing, though the two towers which originally crowned the choir and sacrarium were long ago levelled with the roof of the nave. The material employed throughout the superstructure is red sandstone from the Bharatpur quarries, while the foundations are composed of rough blocks of the stone found in the neighbourhood. These have been laid bare to the depth of several feet; and a large deposit of earth all round the basement would much enhance the appearance as well as the stability of the building.

Bihari Mall, the father of the reputed founder, was the first Rajput who attached himself to the court of a Muhammandan emperor. He was chief of the Rajawat branch of the Kanchhwaha Thakurs seated at Amber, and claimed to be eighteenth in descent from the founder of the family. The capital was subsequently transferred to Jaypur in 1728 A.D.; the present Maharaja being the thirty-fourth descendant of the original stock. In the battle of Sarnal, Bhagawan Das had the good fortune to save Akbar's life, and was subsequently appointed Governor of the Panjab. He died about the year 1590 at Lahor. His daughter was married to prince Salim, who eventually became emperor under the title of Jahargir; the fruit of their marriage being the unfortunate prince Khusru.

The temple has a yearly income of some Rs. 2,300, derived from the two villages, Bhagosa and Lodhipuri, the latter estate being a recent grant, in lien of an annual money donation of Rs. 500, on the part of the Raja of Bharat-pur, who further makes a fixed monthly offering to the shrine at the rate of one rupee per diem. The hereditary Gosains have long devoted the entire income to their own private uses, completely neglecting the fabric of the temple and its religious services.’ [३] In consequence of such short-sighted greed, the votive offerings at this, one of the most famous shrines in Upper India, have dwindled down to about Rs. 50 a year. Not only so, but, early in 1872, the roof of the nave, which had hitherto been quite perfect, began to give way. An attempt was made by the writer of this memoir to procure an order from the Civil Court authorizing the expenditure, on the repair of the fabric, of the proceeds of the temple estate, which, in consequence of the dispute among the shareholders, had for some months past been paid as a deposit into the district treasury and had accumulated to more than Rs. 3,000. There was no unwillingness on the part of the local Government to further the proposal, and an engineer was deputed to examine and report on the probable cost. But an unfortunate delay occurred in the Commissioner's office, the channel of correspondence, and meanwhile the whole of the roof fell in, with the exception of one compartment. This, however, would have been sufficient to serve as a model in the work of restora tion. The estimate was made out for Rs. 8,767; and as there was a good balance in hand to begin upon, operations might have been commenced at once and completed without any difficulty in the course of two or three years. But no further orders were communicated by the superior authorities from April, when the estimate was submitted, till the following October, and in the interim a baniya from the neighbouring town of Aring, by name Chhitar Mall, hoping to immortalise himself at a moderate outlay, came to the relief of the temple proprietors and undertook to do all that was necessary at his own private cost. He accordingly ruthlessly demolished all that yet remained of the original roof, breaking down at the same time not a little of the curious cornice, and in its place simply threw across, from wall to wall, rough and unshapen wooden beams, of which the best that can be said is, that they may, for some few years, serve as a protection' from the weather. But all that was unique and characteristic in the design has ceased to exist; and thus another of the few pages in the fragmentary annals of Indian architecture has been blotted out for ever. Like the temple of Gobind Deva at Brinda-ban, it has none of the coarse figure sculpture which detract so largely from the artistic appearance of most Hindu religious buildings; and though originally consecrated to idolatrous worship, it was in all points of construction equally well adapted for the public ceremonial of the purest faith. Had it been preserved as a national monument, it might at some day, in the future golden age, have been to Gobardhan what the Pagan Pantheon is now to Christian Rome.

References

- ↑ .In Christian mysticism 107 is as sacred a number as 108 in Hindu. Thus the Emperor Justiman's great church of S. Sophia at Constantinople was supported by 107 columns, the number of pillars in the House of Wisdom.

- ↑ In devotional literature manasi has the sense of 'spiritual,' as in the Catholic phrase ' spiritual communion.' Thus it is related in the Bhakt Mala that Raja Prithiraj, of Bikaner, being on a journey and unable to visit the shrine, for which he had a special devotion, imagined himself to be worshipping in the temple, and made a spiritual act of contemplation before the image (murti ka dhyan manasi karte the). For two days his aspirations seemed to meet with no response, but on the third he became conscious of the divine presence. On enquiry it' was found that for two days the god had been removed elsewhere, while the temple was under repair. He then made a vow to end his days at Mathura. The emperor, to spite him, put him in command of an expedition to kabul; but when he felt his end approaching, he mounted a camel and hastened back to the holy city and there expired.

- ↑ The estate is divided into twenty-four bats or shares, allotted among seventeen different families. It appeared that all were agreed as to the distribution, with the exception of one man by name Narayan, who is addition, to his own original share, claimed also as sole representative of a shareholder deceased. This claim was not admitted by the others, and the zamindars continued to pay the revenue as a deposit into the district treasury, till eventually the muafldars concurred in making a joint-application for its transfer to themselves.